CHENNAI: Rolling beedis earns Muthulakshmi, a 60-year-old from Theni, Rs 2,000 a month. But that hardly helps her meet the cost of psychiatric medicines for her 23-year-old son, Muthu Uchumali. She has to rely on the kindness of fellow villagers and also takes up odd jobs to raise the money for the rest of the medicines. Closer to the city, V Jeyasree (21) has to take care of her parents, one of whom is afflicted with a locomotive disorder and the other is a person with mental illness, with the Rs 10,000 she is paid for a data entry job. The family is forced to cut down on expenses, including rationing their groceries and food, to pay medical bills.

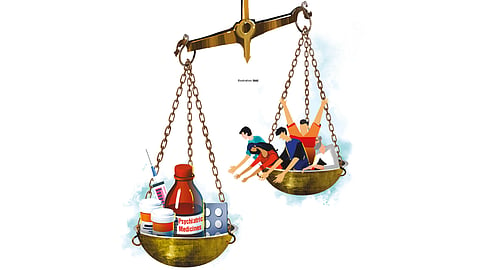

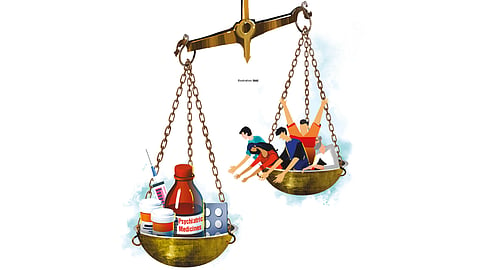

These are just two of several families across the State who face the rather impossible choice between medicines for their disabled family member and limiting all other expenses, including food.

Acknowledging the significance of mental health, the governments at State and Centre have been working on schemes for people with such disabilities. For instance, availing of the Unique Disability Identity Card (UDID) enables them to collect a monthly allowance of Rs 1,000 and medical treatment.

However, as important as this assistance is, it is still not enough for most people with mental illness who have to be under medication, say activists.

“We have had carers of people with mental illness approach us saying they are unable to find psychiatric medicines at government hospitals and are therefore forced to buy medicines from private pharmacies. On average, a person with mental illness requires Rs 3,000 to Rs 6,000 a month only on medication. The allowance they receive definitely does not help in covering the expenditure,” Vaishnavi Jayakumar, member, Disability Rights Alliance, told DT Next.

Another trouble that the scheme’s beneficiaries face is the availability and accessibility of psychiatric medicines. While people in the city have the means to get medicines, it is far from easy for those away from urban centres.

A Livingston from Tiruvallur, president of Vasantham Federation of Differently-Abled Persons, said getting medicines for those with mental illness is one of the major hurdles at the primary level. “Government hospitals do not have a steady supply of psychiatric medications and these are also not available at general pharmacies. So people are forced to travel 40 km to Chennai or Ayanavaram (to the Institute of Mental Health) for their medicines, which ends up blowing a hole in their pockets,” he said.

The National List of Essential Medicines (NLEM) 2022 lists 13 psychotropic drugs that should be available at primary, secondary and tertiary levels. While the GH and medical colleges have insufficient stock, the Makkal Marundhagam generic medicine centres in the North, Central and South zone do not have all the medicines.

When asked the reason for the shortage, a person who works in the field explained that when the rate contract between the medicine supplier and the distributor to supply items for a fixed unit price expires each year, it often takes two to three months to renew the contract. During this period, these medicines are available in adequate stock, he said.

That is not all. Even those who are able to buy medicines from private pharmacies often find that it is close to impossible due to a reason that has nothing to do with affordability, accessibility or availability.

When patients go to government hospitals, they get a small notebook on which their names and the names of the medicines are written. “But this notebook prescription works only at the particular government hospital. When that hospital doesn’t have stock, patients cannot go to pharmacies outside and buy them because these medicines will not be given without a proper prescription,” said D Kotteswara Rao, assistant director of SCARF, a nonprofit mental health centre in Chennai.

When asked, Tamil Nadu Medical Service Corporation (TNMSC) managing director Deepak Jacob said there was sufficient stock in government hospitals and medical colleges. “However, it is difficult to stock up on speciality psychiatric drugs because these medicines do not have a definite user pattern. Therefore, this leads to issues with restocking medicines,” he said.

UDID: SWEETENING IT UP A LITTLE

WHAT IS IT: The Unique Disability Identity Card project was initiated by the Department of Empowerment of Persons with Disabilities in 2016.

FOR WHOM: The ID is given to people with locomotive disability (LD), leprosy, cerebral palsy, dwarfism, muscular dystrophy, acid attack survivors, visual and hearing impairment, intellectual disabilities, mental illness and so on.

HOW MUCH: Cardholders get a monthly allowance of Rs 2,000 for LD and Rs 1,000 for mental illness. Through the card, they can also avail of medicines and other benefits under this scheme.

WHERE TO: Citizens can apply online at https://www.swavlambancard.gov.in/ and track the status of their card. However, as per the performance budget of 2022 by the State government, only 53.8 per cent of applicants in Tamil Nadu have received UDIDs.

Visit news.dtnext.in to explore our interactive epaper!

Download the DT Next app for more exciting features!

Click here for iOS

Click here for Android