Prez reference: Will apex court answer Droupadi Murmu?

CHENNAI: It has been over a month since President Droupadi Murmu asked for an advisory opinion from the Supreme Court, sending 14 queries revolving around the discretionary powers bestowed on the President and the Governor under the Constitution. When we say the President is seeking an opinion, it is the opinion sought by the cabinet headed by Prime Minister Modi. Under Article 74, the President cannot act without the aid and advice of the Central cabinet headed by the Prime Minister. There used to be a time when one understood that the President had certain discretion in discharging his/her duties. However, the 42nd Amendment of the Constitution has put a seal on any such discretion, and the President merely acts like a post office.

Then the question will be why the central cabinet wanted opinion from the Supreme Court on matters of the discharging duties of the President and Governors from the Supreme Court. Naturally, one will ask why the central cabinet needs a legal opinion when it has a battery of legal advisors and a well-established law ministry under its control. The Attorney General of India, who holds the constitutional office under Article 76, has his duty to advise the President and the government.

After the judgment rendered in the case filed by Tamil Nadu, a two-judge bench headed by Justice Pardiwala in no-nonsense terms said neither the Governor nor the President can withhold any Bill without giving assent eternally and put a three-month time limit to decide the question of giving assent to a Bill sent by a state legislative assembly under Article 200 and 201 of the Constitution. Not stopping with its legislative fiat, having found Governor Ravi had unreasonably delayed giving the assent for more than a year without any explanation, the Supreme Court, exercising its extraordinary power conferred under Article 142, gave the assent itself.

Such a move by the Supreme Court might have sent shockwaves to those holding gubernatorial posts, thinking they were wielding unchecked powers and there was no one to question them. Little do they realise that there is something like the Constitution, which is the rule book for exercising powers by persons in authority. It is not as if the Constitution did not talk about any time limit for giving assent to the Bills sent by the State legislature. On the other hand, the legislature represents the will of the people through its elected legislators, and the executive head of the state, like the Governor, cannot treat the legislature as a subordinate authority. The proviso to Article 200 mandates that when the Bill is sent for assent by the Governor, he must “as soon as possible” either return the Bill with a message requesting the legislature to reconsider and in case the House returns the Bill with or without change, he shall give the assent.

While granting assent for any Bill, the Governor or the President does not exercise the power of an umpire but only acts as an authentication authority. Over a period, the Governors sent by the Home Ministry have started acting in a manner not conducive to the smooth functioning of the State; on the other hand, they play the role of an opposition party, destabilising the elected state governments. This political game involved granting delayed assent or acting without the aid and advice of the state cabinet headed by the Chief Minister.

It is not as if the law passed by the State legislature will have the last word on the issue. Any citizen at any point in time can even institute a suit in the smallest civil court challenging the constitutional validity of such a law. There is no time limit for such a challenge, and whenever a citizen is faced with an unconstitutional legislative provision, s/he could make a challenge. Starting from the court of munsif to the highest court in India, i.e. the Supreme Court, all courts have been conferred with the power of judicial review over any legislation. So far, no court has ever found either the Governor or the President at fault for giving assent to any Bill passed by the Parliament or the state legislatures.

Since the Constitution has prescribed the least qualifications for holding the post of Governors, and they only function at the pleasure of the President, i.e. the Cabinet, one may think that they may not understand the nuances of a constitutional issue behind any state legislation. In such a situation, it is always open to the Governor to seek legal opinion and in no case can s/he delay giving assent to the Bill, thinking s/he was either the monarch of the United Kingdom or the all-powerful President of the United States. Even during the debates in the constituent assembly, while discussing the scope of power of the Governor, it was made clear that the Governor is conceived to play a ceremonial role and, at times, the role of an advisor to the state.

When the Supreme Court fixed an outer time limit of three months to grant an assent, there was nothing of any infringement or intrusion into the powers of the governors. It is not the first time the Supreme Court has chosen to fix time limits for the governors or the President to act. When persons facing the death penalty seek reprieve under the mercy powers of the President (Article 72) and Governors (Article 161), any delay in making a decision will make the convicts go through the ordeal of facing death every day, and that would amount to a double penalty. In such circumstances, the Supreme Court held that either the President or the Governor shall dispose of the mercy petitions within six months.

As early as 1974, in the famous Shamsher Singh case of a district judge being removed by the Punjab Governor without any cabinet advice, a bench of seven judges held that a Governor cannot act on his/her own in passing a dismissal order, and without the aid and advice of the State cabinet. In the same case, instead of sending the issue for reconsideration by the Governor, which in normal circumstances the court always does, the Supreme Court applied the “useless formality theory” and gave relief to the affected by exercising power under Article 142, which empowers the top court to do full and effective justice in any matter dealt with by them. It was in that way that Justice Pardiwala's bench also granted assent to the pending Bills to the Governor.

Then why create such a hue and cry in a matter of this nature? The curious question is, while Article 137 provides for a review of any order passed by the Supreme Court, why did the Modi government file a review application if the Tamil Nadu case was legally unsound? Apart from the review power, the Supreme Court itself has evolved another method of relief, being the highest and final court, which is called a “curative petition”. Under this, if two senior advocates certify that it was a fit case for reconsideration and cite sufficient reasons, the Supreme Court, notwithstanding the finality attached to its order, can still reconsider the matter by constituting a special bench.

It was also curious to note that when the Kerala government wanted to withdraw a similar case filed against the Governor, citing that the Tamil Nadu judgment would also apply in their case, the same was stoutly opposed by the Modi government, and the case is pending. If the Modi government wanted to assail the Tamil Nadu judgment as legally not valid, it could always raise the issue in the Kerala case.

The timing of posing the queries before the Supreme Court by the Modi government has also raised little discomfort. Even when the government was busy after the Pahalgam attack and was preparing for Operation Sindoor, what was the urgency of seeking the advisory opinion of the Supreme Court? First of all, an opinion given by the Supreme Court under Article 143 is not binding on anyone. If necessary, the court can even refuse to give any advice, which it has done several times before.

Though a month has gone by, the Supreme Court has not responded to the request, maybe because it is on a summer recess or there is a recent change of guard in the post of Chief Justice of India. The court will have to say one way or the other when requesting an advisory opinion. In any event, since the last 75 years of its existence, the Supreme Court has dealt with several cases of powers exercised by the President or the governors. If only the Modi government had studied those precedents, the present attempt to seek opinion, which is more of a political stunt and a wasteful academic exercise, could well have been avoided.

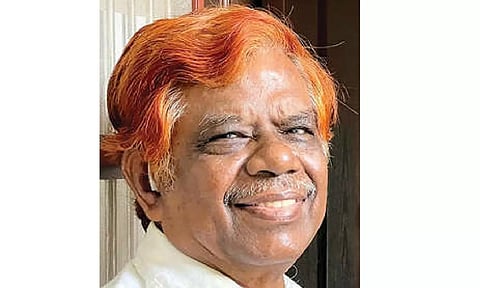

The writer is a retired judge of the Madras High Court