Charles Murray’s new book, Taking Religion Seriously, in which he explains his move from atheism to a heterodox Christianity, offers a distinctive reading experience for me. This year, I published a book arguing that it should be possible to reason one’s way from skepticism to belief, tracing arguments a doubter might follow across the threshold of faith.

What I proposed, Murray’s book explicitly embodies. It’s an intellectual memoir in which the author, through years of reading and debate, thinks his way into religion, following many of the same signposts I recommended — from scientific discoveries to supernatural evidence to New Testament interpretations.

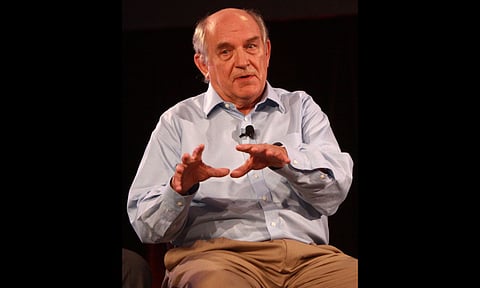

While promoting my book, I was often asked whether someone outside religious faith could make this kind of journey intellectually — whether argument alone could persuade anyone of religious claims. Now I can hand them Murray’s book and answer affirmatively, with the caveat that Murray, a prominent conservative policy thinker married to a Quaker and long immersed in circles of religious intellectuals, is an idiosyncratic case study.

Rather than simply discuss the convergences between our arguments, reading Murray’s book and agreeing with much of it made me reflect on the resilience of skepticism.

Christmas invites such contemplation, insofar as it is itself an argument for belief: a seemingly obscure birth within a great empire that redirected two millenniums of human history, introducing a story and system of values whose influence extends even to nonbelievers. And yet, according to Christian tradition, this decisive event happened once, and only a few witnessed its fullness — Mary, Joseph, a handful of shepherds, several learned observers from afar. That is assuming the infancy narratives are strictly historical, which some believers, including Murray, doubt even if they accept the broad historical credibility of the Gospels.

What applies to an extreme religious event like Christmas applies also to much supernatural evidence. Even when the data for belief appears persuasive, one can imagine a world where it was more persuasive still — where God’s existence was marginally clearer, skepticism had fewer refuges, and religious argument more authority.

Take evidence for consciousness as something not reducible to matter — capable of surviving in some form after death. Murray’s book and mine both outline reasons to take this view seriously, from experience to philosophy to science to reports at the edges of perception and mortality.

Consider one example Murray discusses: terminal lucidity, in which people suffering catastrophic cognitive decline unexpectedly regain clarity shortly before death. His treatment of this phenomenon prompted debate about whether such returns are physiologically inexplicable. But even if terminal lucidity fits better in a theistic worldview, it has a notable feature: not everyone experiences it. It may be more common than medicine recognizes, but families of Alzheimer’s or dementia patients cannot depend on it. It appears selectively, more like a grace than a predictable occurrence.

Why must it be unpredictable? If terminal lucidity strengthens the case for consciousness’s independence from matter, why not grant it universally — offering all caregivers a final moment of recognition, all sufferers a last chance to recover themselves? It would also offer religious arguers potent evidence in trying to convince skeptics that the soul exists.

One answer is that it might not matter much. Short of a world in which God is unmistakably apparent and freedom overwhelmed, no degree of evidence may eliminate the will to disbelieve. Examples exist of people with direct encounters that do not lead to conversion. Perhaps even some who witnessed angelic choirs returned to sleep.

Still, after spending much of 2025 arguing religion, I can imagine certain “dials” God could turn that would make my position stronger. I would welcome, for instance, a few contemporary versions of the 17th-century saintly levitators.

In their absence, the reasonable religious conclusion is that skepticism, like suffering, belongs to the divine plan — that the universe’s created goodness includes space for creatures who believe it was not created.

Which means that neither Charles Murray nor I should become overconfident in our shared insights or too disappointed when readers find them unconvincing. The settling of these debates, like the announcement of a birth two millenniums ago, belongs to powers beyond our own.

The New York Times