The end is nigh. This fall, it feels nigh-er than usual.

In the last three months, the drumbeat of end times seems to have grown louder: first, rumours of the Rapture; second, harbingers — or at least one — of apocalypse; and throughout, a thrumming sense of general unease.

This is both nothing new and worthy of note. End-times predictions are perennial and, so far, always wrong. So why do we keep indulging in them?

In recent decades, Americans have obsessed over potential disasters because of overpopulation (still yet to occur); nuclear war (as yet avoided); Y2K system breakdown (a blip); societal collapse owing to a global pandemic (not quite); and a still-looming climate crisis (results to be determined).

But today, whether thanks to the extraordinary chaos of the second Trump presidency, alarming advances in artificial intelligence or something else, the spread between reality and apocalypse feels less pronounced.

In September, rumours spread on TikTok that the apocalypse would begin in the second half of the month. Some evangelical Christian content creators predicted that Jesus Christ would return on Sept. 23 to take his true followers to heaven, leaving the unfaithful behind. Videos about the Rapture — some made in jest, some definitely not — got many millions of views before the appointed date passed. (Spoiler: The Rapture did not occur.)

Not to be outdone in panic, billionaire tech investor and political influencer Peter Thiel spent the fall popularising his long-held theory that Armageddon was on its way and perhaps already here. In a closed-door, four-part lecture series in San Francisco, he shared musings on Bill Gates and international finance, speculations on the danger of a one-world state and his feeling that an “Antichrist-like system” was primed for activation “at the flip of the switch.”

Even in a nonreligious context, feelings of looming catastrophe abound. A poll from Brookings and the Public Religion Research Institute found that 62% of Americans believe things are going in the wrong direction, with 56% believing President Trump is a “dangerous dictator whose power should be limited before he destroys American democracy.” A 2022 Pew poll found that nearly four in 10 Americans believe that humanity is “living in the end times”; it is hard to imagine that number shrinking after the distress of the past several years.

Underneath it all has been a consistent drumbeat of doom from Silicon Valley, where executives and researchers issue gloomy yet triumphant predictions that A.I. is on its way to overtaking humans and perhaps destroying us all. “If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies” is the title of a new book from A.I. researchers Eliezer Yudkowsky and Nate Soares — not a comforting statement, considering the number of trillion-dollar companies seeking to build such systems as fast as they can.

Many of today’s end-times anxieties echo those from similar moments in the past: rumours of apocalypse are often loudest when one way of life threatens to overtake another. Dispensational theology, the literalist biblical interpretation that first popularised the concept of the Rapture, emerged in mid-19th-century Britain as the Industrial Revolution transformed society and found purchase in the United States after the chaos of the Civil War.

Explanations of the coming eschaton, or end, were attempts to seek certainty in an uncertain time, whose parallels with this moment are straightforward: rapid social change, economic confusion, fears of conflict and historic technological shifts that left roles unsettled and the future up for grabs.

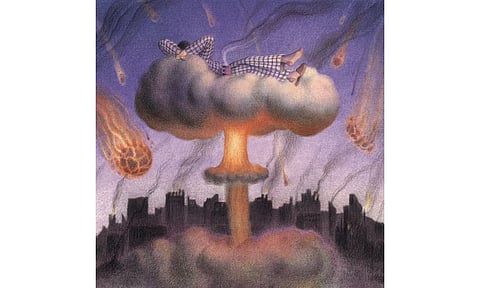

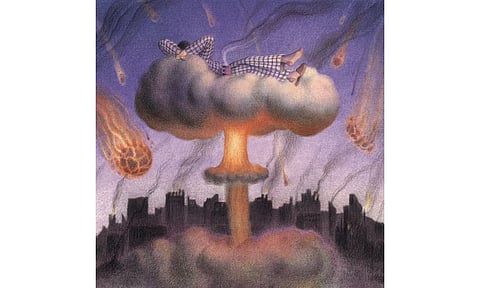

In previous centuries, apocalypse was discussed mainly in religious contexts — the Rapture separating righteous wheat from evildoing chaff — while today the idea of mass destruction holds a certain mass appeal. However scary Armageddon might be, it would come for us all. The result would be true justice served, a terminus to the pain that modern existence entails.

Our thoughts may turn to the end of things when it feels as though the current moment can’t be lived through: events seem too chaotic, too unpredictable; the forces individuals face feel too large to tackle. The more hopeful among us are comforted by the idea that a rescue is on the way (perhaps Jesus returning for his chosen people, a very literal deus ex machina); the rest wait with anxiety, killing time by making predictions about what form the end will take. Either way, certain destruction can seem more bearable than limbo.

But that certainty — or at least pessimism — can be paralysing. Why vote when a “dangerous dictator” is already at the helm? Why try to regulate a technology assumed powerful enough to turn the world’s resources into paper clips? Why improve the world if it’s ending tomorrow?

Apocalyptic predictions may serve as comforting fantasies, excuses for inaction that end up hastening the feared outcomes.

It’s easier to assume the world is ending than to do the work needed to make sure that it’s not.

@The New York Times