• ANNA HOLMES

NEW YORK: I had my first conscious interaction with Ms. magazine as a small child when I read — or rather, had read to me — a story-poem called “Black Is Brown Is Tan.”

Part of the magazine’s delightful kids’ section, “Black Is Brown Is Tan” is about a mixed-race family not unlike my own who go about their daily routines like any other Americans. Though I was young, I remember the illustrations, by Emily Arnold McCully, with acute clarity: the rosy cheeks of the white dad, the short Afro and hoop earrings of the Black mom, and, perhaps most important, the sense of safety and warmth that permeated every page. In our house, where my mother was careful about the messaging of the media and toys we consumed, the “Stories for Free Children” section was always welcome. As for the magazine they appeared in? Well, it was canon.

Of course, what older readers probably remember are the magazine’s bread and butter, all those unapologetically feminist features and sidebars that combined the political with the personal and boasted bylines like Audre Lorde, Barbara Ehrenreich, Susan Brownmiller and Eleanor Holmes Norton. Containing stories on everything from the question of equal pay to the politics of body hair, “50 Years of Ms.” provides a snapshot of the issues facing many American women from the 1970s on, including the concerns and contributions of Black women to the 20th-century feminist and political project.

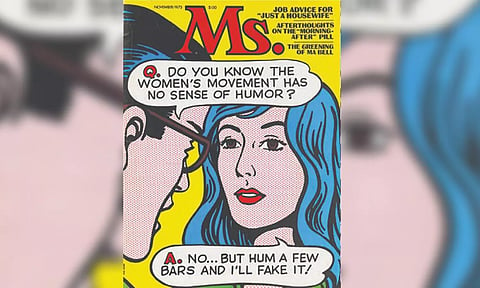

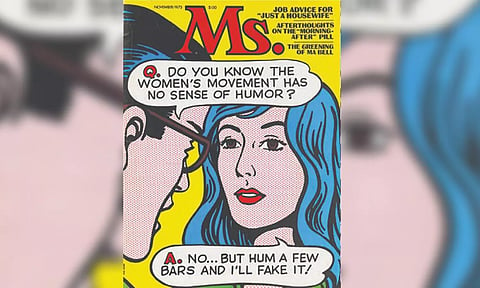

It began as an insert in New York magazine, featuring a famous cover story titled “Click! The Housewife’s Moment of Truth,” about ah-ha! moments centering on sexism and misogyny. First a monthly, later a quarterly, Ms. was famously co-founded by the writer and activist Gloria Steinem, who contributes a foreword. The question, of course, is how all this reads in 2023.

Ms. was often prescient, anticipating and exploring topics that feel just as relevant today as they did at the time of writing, including misinformation about menopause (1993), the harmful effects of pornography (2004) and the controversies and tensions surrounding the evolution of personal pronouns (1985). Under the headline “The Search for Signs of Intelligent Life in the Twenty-First Century” in 1990, a wry Jane Wagner predicts that the feminist movement “for the umpteenth time will be pronounced dead,” the only three types of remaining government will be “neo-fascism, regular fascism and fascism lite” and that the “flesh-coloured Band-Aid will come in many colors.”

As for what Ms. didn’t get quite so right? That’s harder to determine — understandably, “50 Years of Ms.” has been edited and curated so that the magazine is painted in the best possible light. As such, any of its missteps appear few and far between, though that was hardly the case in reality. In 1986, after the publication of a cover showing two pregnant white women, the author Alice Walker resigned from the masthead, citing the magazine’s lack of diversity.

Which brings me to my biggest criticism: Elements of this compendium feel weirdly rooted in the past. Perhaps that’s unfair, considering what the book primarily is — a commemoration of a legacy. But I was surprised and disappointed that the blurbs on the back cover didn’t include any from women (or men) under the age of 60.