By Edmund S. Higgins, Affiliate Associate Professor ofPsychiatry & Family Medicine, Medical University of South Carolina Charleston,Oct 1 (The Conversation) The possibility of precious objects hidden in secretchambers can really ignite the imagination. In the mid-1960s, British engineer Godfrey Hounsfield ponderedwhether one could detect hidden areas in Egyptian pyramids bycapturing cosmic rays that passed through unseen voids.

He held onto this idea over the years, which can beparaphrased as “looking inside a box without opening it.” Ultimately he didfigure how to use high-energy rays to reveal what’s invisible to the naked eye.He invented a way to see inside the hard skull and get a picture of the softbrain inside.

The first computed tomography image – a CT scan – of thehuman brain was made 50 years ago, on October 1, 1971. Hounsfield nevermade it to Egypt, but his invention did take him to Stockholm andBuckingham Palace.

An engineer’s innovation Godfrey Hounsfield’searly life did not suggest that he would accomplish much at all. He was not aparticularly good student. As a young boy his teachers described him as“thick.” He joined the British Royal Air Force at the start ofthe Second World War, but he wasn’t much of a soldier. He was, however, awizard with electrical machinery – especially the newly invented radar that hewould jury-rig to help pilots better find their way home on dark, cloudynights.

After the war, Hounsfield followed his commander’sadvice and got a degree in engineering. He practiced his trade at EMI – thecompany would become better known for selling Beatles albums, butstarted out as Electric and Music Industries, with a focus on electronics andelectrical engineering.

Hounsfield’s natural talents propelled him to lead the teambuilding the most advanced mainframe computer available in Britain. But by the‘60s, EMI wanted out of the competitive computer market and wasn’t sure what todo with the brilliant, eccentric engineer.

While on a forced holiday to ponder his future and what hemight do for the company, Hounsfield met a physician who complainedabout the poor quality of X-rays of the brain. Plain X-rays show marvelousdetails of bones, but the brain is an amorphous blob of tissue – on an X-ray itall looks like fog. This got Hounsfield thinking about his old ideaof finding hidden structures without opening the box.

A new approach reveals the previously unseen Hounsfield formulateda new way to approach the problem of imaging what’s inside the skull.

First, he would conceptually divide the brain intoconsecutive slices – like a loaf of bread. Then he planned to beam a series ofX-rays through each layer, repeating this for each degree of a half-circle. Thestrength of each beam would be captured on the opposite side of the brain –with stronger beams indicating they’d traveled through less dense material.

Finally, in possibly his most ingenious invention, Hounsfield createdan algorithm to reconstruct an image of the brain based on all these layers. Byworking backward and using one of the era’s fastest new computers, he couldcalculate the value for each little box of each brain layer. Eureka! But therewas a problem: EMI wasn’t involved in the medical market and had no desire tojump in. The company allowed Hounsfield to work on his product, butwith scant funding. He was forced to scrounge through the scrap bin of theresearch facilities and cobbled together a primitive scanning machine - smallenough to rest atop a dining table.

Even with successful scans of inanimate objects and, later,kosher cow brains, the powers that be at EMI remained underwhelmed. Hounsfield neededto find outside funding if he wanted to proceed with a human scanner.

Hounsfield was a brilliant, intuitive inventor, but not aneffective communicator. Luckily he had a sympathetic boss, Bill Ingram,who saw the value in Hounsfield’s proposal and struggled with EMI to keep theproject afloat.

He knew there were no grants they could obtain quickly, butreasoned the U.K. Department of Health and Social Security couldpurchase equipment for hospitals. Miraculously, Ingram sold them fourscanners before they were even built. So, Hounsfield organised ateam, and they raced to build a safe and effective human scanner.

Meanwhile, Hounsfield needed patients to try outhis machine on. He found a somewhat reluctant neurologist who agreed to help.The team installed a full-sized scanner at the Atkinson Morley Hospital in London,and on Oct. 1, 1971, they scanned their first patient: a middle-aged woman whoshowed signs of a brain tumour.

It was not a fast process – 30 minutes for the scan, a driveacross town with the magnetic tapes, 2.5 hours processing the data on an EMImainframe computer and capturing the image with a Polaroid camerabefore racing back to the hospital.

And there it was – in her left frontal lobe – a cystic massabout the size of a plum. With that, every other method of imaging the brainwas obsolete.

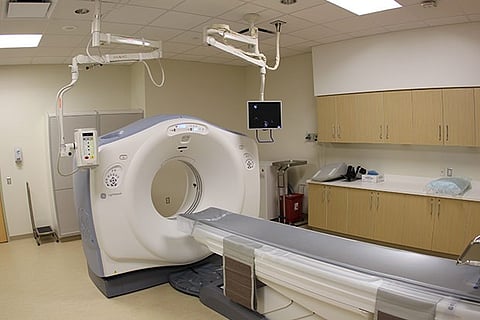

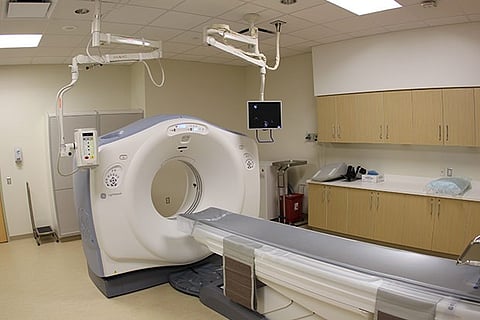

Millions of CT scans every year EMI, with no experience inthe medical market, suddenly held a monopoly for a machine in high demand. Itjumped into production and was initially very successful at selling thescanners. But within five years, bigger, more experienced companies with moreresearch capacity such as GE and Siemens were producing betterscanners and gobbling up sales. EMI eventually exited the medical market – andbecame a case study in why it can be better to partner with one of the big guysinstead of trying to go it alone.

Hounsfield’s innovation transformed medicine. He sharedthe Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1979 and wasknighted by the Queen in 1981. He continued to putter around with inventionsuntil his final days in 2004, when he died at 84.

In 1973, American Robert Ledley developed awhole-body scanner that could image other organs, blood vessels and, of course,bones. Modern scanners are faster, provide better resolution, and mostimportant, do it with less radiation exposure. There are even mobile scanners.

By 2020, technicians were performing more than 80 millionscans annually in the U.S.. Some physicians argue that number is excessive andmaybe a third are unnecessary. While that may be true, the CT scan hasbenefited the health of many patients around the world, helping identifytumours and determine if surgery is needed. They’re particularly useful for aquick search for internal injuries after accidents in the ER.

And remember Hounsfield’s idea about the pyramids? In 1970scientists placed cosmic ray detectors in the lowest chamber in the Pyramid ofKhafre. They concluded that no hidden chamber was present within the pyramid.In 2017, another team placed cosmic ray detectors in the Great Pyramid of Gizaand found a hidden, but inaccessible, chamber. It’s unlikely it will beexplored anytime soon. (The Conversation) RS RS

Visit news.dtnext.in to explore our interactive epaper!

Download the DT Next app for more exciting features!

Click here for iOS

Click here for Android