Chennai

India will need to bring in an Urban Employment Guarantee Act to resolve the problem of rising levels of unemployment and to ensure that educated youth are gainfully employed. This should be in addition to the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA), recommended a report.

The State of Working in India (SWI) – 2019 report prepared by the Azim Premji University recommends a National Urban Employment Guarantee Programme (NUEGP) that will strengthen small and medium-sized towns by providing a legal right to employment. But, it has also established a rural-urban paradox, with unemployment in urban India being higher at 7.8 per cent, than the 5.3 per cent in rural India.

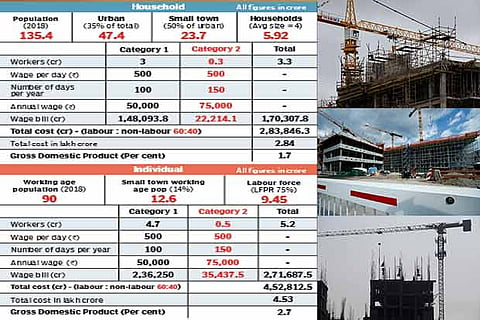

As per the leaked Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) 2017-2018 of the National Sample Survey Office (NSSO), the open unemployment in India had hit a historic high of 6.1 per cent, with a striking 20 per cent unemployment among the educated youth.

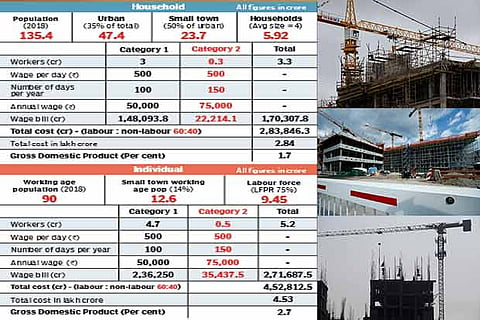

Taking into account the estimated population of 135 crore in 2018, and applying an urbanisation rate of 35 per cent puts the total urban population at 47.4 crore. Assuming that approximately 50 per cent of the urban population resides in towns of less than 10 lakh population, we get a small-town population of 23.7 crore. With an average of four members in an Indian household, the report estimates 5.9 crore households. One worker from each household gives a total possible workforce of 5.9 crore (see graphic).

The NUEGP envisages 100 days of guaranteed employment at wages of Rs 500 per day, and also makes a provision for 150 contiguous days of training and apprenticeship at a stipend of Rs 13,000 per month for educated youth.

The report categorises workers into two types – Category 1 workers who are educated up to Class 12 and have other informal skills and work as construction labour, painters, electricians and so on.

Category 2 workers who have a formal degree or diploma, including industrial training diplomas, certificate courses in computing and English skills (see graphic).

Backed by a job-card that will electronically update work done, demographics, bank and wage-payments, and professional details of an individual, this scheme will not only provide guaranteed number of days of employment at a defined wage, but is also expected to kick-off a multiplier effect, the Azim Premji University report states.

The demand driven workforce could be deployed productively (as waged workers compared to just being a beneficiary under other schemes). That in turn would improve the quality of delivery of government services, maintain and develop infrastructure in Indian cities, push-up local demand for goods and services, spur local entrepreneurship, and would build skills that could address the “employability crisis” being faced by the private sector.

In order to have a real impact on the ground, the NUEGP will have to be backed by an Act, that will make it a “statutory right to employment”, just like the rights-based framework of MGNREGA. The SWI report makes it clear that this programme should not be at the cost of MGNREGS which is aimed at generating employment in rural areas, but rather complement it, as NUEGP applies to urban-unemployed.

India is not alone. Interestingly, even in developed countries like the US, employment guarantee forms a crucial component of the ‘Green New Deal’, a series of policy proposals for addressing climate change and economic inequality, advocated by many Presidential candidates. The ‘Green Job Guarantee’ entails a legal right, that makes it obligatory for the federal government to provide a job to anyone who asks for one, and to pay them a liveable wage. This Green New Deal proposes public expenditure of up to 8-10 per cent of US GDP.

Compared to the US, the National Urban Employment Guarantee Programme is estimated to cost the Indian exchequer anywhere between 1.7-2.7 per cent of GDP, depending on the options exercised, either one adult from every household or every unemployed individual in the workforce. The total number of unemployed individuals are estimated to be between 3-5 crore in India’s small towns.

The newly elected Madhya Pradesh government has recently launched Yuva Swabhiman Yojana, a 100-day urban job guarantee scheme.

Kerala too has been running AUEGS (Ayyankali Urban Employment Guarantee Scheme) since 2010, guaranteeing 100 days of wage employment to an urban household for manual work.

NUEGP is also designed to be administered and monitored by the Urban Local Body (ULB) like the Municipal Council, or Municipal Corporation and Nagar Panchayats. These urban bodies responsible for implementing this scheme would be financed by a pool of Central and state government funds. It covers about 4,000 Urban Local Bodies, accounting for about 50 per cent of the urban population as per the2011 Census.

-News Research Department

Cost implication

The total budgetary requirement or the costs would be divided under three heads: labour, material, and administrative costs, with a proposed formula of 60% of the total allocation for labour cost and 40% for material and administrative costs combined. Further Labour costs are designed to be split between the Centre and the States in an 80:20 ratio. And the remaining non-labour costs would be shared between the Centre, the state government, and the ULBs. In case of Type 1 cities, the smallest and most resource constrained, the non-labour costs will be shared between the Centre, state and ULB in the ratio of 50:40:10. For Type 2 cities it will be in the ratio of 50:30:20 and Type 3 cities, the largest, in the ratio of 50:25:25

A few examples of urban livelihood options

Waterbodies (ponds, tanks, lakes)

Construction of smaller tanks in lakes

Maintenance of bunds, de-weeding, desilting,

garbage/waste removal

Fencing or repairing boundary walls and fences

Wetlands

Cleaning weeds and garbage

Reclaiming and rejuvenating wetlands

Coast/beachfronts

Construction, maintenance of mangroves wher ever possible

Construction and maintenance of cyclone

shelters

Fish drying and processing sites

Parks (large and small neighbourhood parks)

Planting appropriate vegetation

Focus on less landscaping and more planting

of trees

Playgrounds and open spaces

Construction of facilities for different games in

playgrounds and maintenance

Alongside railway lines

Planting ecologically suitable local species of

trees where relevant, maintenance

Slums

Individual and community farming, creating

kitchen gardens with medicinal plants and

greens to supplement nutrition

Government schools and anganwadis

Construction of rainwater harvesting and

storage facilities

Planting appropriate vegetation,

maintenance

Land use mapping of all common and public lands in the ward

Regular survey of all common and

public lands

Tracing boundaries using GPS points and

marking land use features (for example Lake inlets and outlets)

Mapping waste dumps and stagnant water pools

Collecting information on waste sites and water

pools to ensure that they are addressed to

control disease

Social interviews with local residents and users of commons/public lands

Interviews with those who use common and

public lands for livelihood and subsistence to

monitor changes to use and understand causes and to provide information that can be

used for rejuvenation works

Data entry

Updating data collected in the ward from

surveys and mapping for use by the municipal

offices and other government institutions

Type 1 towns(Up to 50,000 population)

Adoor (Municipality), Kerala

Kovvur (Municipality), Andhra Pradesh Kalimpong (Municipality), West Bengal

Mapusa (Municipal Council), Goa

Rameswaram (Municipality), Tamil Nadu

Vadnagar (Municipality), Gujarat

Type 2 towns (50,000 - 3,00,000 population)

Anantapur (Municipal Corporation), Andhra Pradesh

Gandhinagar (Municipal Corporation), Gujarat

Kottayam (Municipality), Kerala

Raichur (City Municipal Council), Karnataka

Thanjavur (Municipal Corporation), Tamil Nadu

Type 3 towns (300,000 - 10,00,000 population)

Bhubaneswar (Municipal Corporation), Odisha

Erode (Municipal Corporation), Tamil Nadu

Kurnool (Municipal Corporation), Andhra Pradesh

Salem (Municipal Corporation), Tamil Nadu

Thiruvananthapuram (Municipal Corporation), Kerala

Visit news.dtnext.in to explore our interactive epaper!

Download the DT Next app for more exciting features!

Click here for iOS

Click here for Android