Chennai

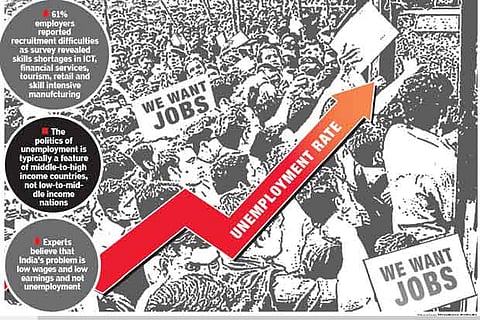

In the season of intense political battles, one topic that has been the bone of contention and fuelled the bitterest of poll-debates, is the problem of rising unemployment in India, especially during the NDA regime. The ruling NDA government has aggressively defended its position by stopping National Sample Survey Office (NSSO) from releasing data on unemployment and stating that these allegations are not based on facts, and put forward a proposed study of employment generated under MUDRA (Micro Units Development and Refinance Agency) schemes.

Right in the middle of these ongoing controversies raised by various political parties, CSE (Centre for Sustainable Employment) of Azim Premji University, on April 16, 2019, has come out with its “State of Working India (SWI) 2019”, an analysis of the unemployment problem, with a potential formula to generate mass employment in the country.

A couple of the key findings are that 60 per cent of the educated youth in the 20-24 age group is unemployed and that the country's unemployed are mostly the higher educated and the young.

Among urban men, the 20-24 age group accounts for 13.5 per cent of the working age population, but 60 per cent of the unemployed. In addition to rising open unemployment among the higher educated, the less educated, mostly informal workers have also seen job losses and reduced work opportunities since 2016.

The data-analysts have pointed out that the data on women in urban areas show that graduates are 10 per cent of the working age population, but 34 per cent of the unemployed.

Youth today are much better educated than their parents. According to the 2015 Employment-Unemployment Survey of the Labour Bureau, workers with no formal education at all are now 12 per cent of the labour force. The enrolment rate for secondary education reached 90 per cent in 2015. The enrolment rate for higher education in the 18-23 age group rose to 26 per cent in 2016 from 11 per cent in 2006.

While there have been many arguments and counter arguments against the non-release of NSSO data, as per the SWI report, the biggest challenge has been the lack of systematic data on the topic. The SWI, right from the beginning points out the lack of systematic availability of labour and unemployment statistics. India’s labour data has neither been timely nor forthcoming.

The last NSSO employment survey was in 2011-12 and Labour Bureau Survey was in 2015. The new higher frequency, quarterly and annual Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) has also not been made public. Therefore, the analysis in SWI by Azim Premji University depends on data from CMIE surveys to describe the current job scenario.

How real is this unemployment problem in India?

As per SWI, India’s working population has increased from 95.8 crore in 2016 to 98.31 crore in 2018, with the marked rise in unemployment since 2011, whichever household survey that was studied (LB-EUS, PLFS, or CMIE-CPHS).

The survey found that those with higher-education and the young outnumbered the unemployed. In addition to open unemployment among the educated, the less educated, and likely informal, have also seen job losses and reduced work opportunities over this time period. One striking feature in SWI is women were worse off than men in respect to the levels of unemployment as well as reduced labour force participation.

Between the third wave of 2016 and the third wave of 2018, the urban male workforce participation rate (WPR) fell by 3.6 percentage to 65.5 per cent from 69.1 per cent. For the same period, the rural male WPR fell by 3.2 percentage to 68.6 per cent from 71.8 per cent.

All India (rural and urban) male WPR fell by 3.3 percentage in this period. What does a 3.3 percentage decline in the WPR mean in terms of jobs lost? We can answer this question by drawing on the population estimates provided by the UN Department of Economics and Social Affairs.

As per these data, the male working age population in India increased by 1.61 crore between 2016 and 2018. Accounting for the increase in working age population, the decline in the WPR amounts to a net loss of 50 lakh jobs during this period. Recall that this analysis applies to men only. When we take women into account, the number of jobs lost will be higher.

According to the statistics of PLFS (Periodic Labour Force Survey), 2017-2018 data that was leaked and made headlines, open unemployment hit a historic high of 6.1 per cent, with educated-unemployed youth touching a level of 20 per cent. The urban unemployment stood at 7.8 percent, higher as compared to 5.3 percent unemployment rate in rural areas.

CMIE estimates peg the unemployment figure as 50 lakh Indians, who lost their jobs between 2016 and 2018, coinciding with demonetisation in November 2016. But, many experts differ on the cause-effect factors, as no direct or causal relationship have been established between trends of rising-unemployment and demonetisation, based only on these trends. To strengthen the towns through a sustainable employment programme, the Azim Premji University study has proposed a job guarantee programme for urban India, modelled on MGNREGA. The proposal talks of providing 100 days of guaranteed work at Rs 500 a day for a variety of works. It also provides for 150 continuous days of training and apprenticeship at a stipend of Rs 13,000 per month for educated youth.

Strengthening towns through sustainable employment: A national urban job guarantee programme that can change the scenario for ever

Public works

Building, maintenance and upgradation of civic infrastructure like roads, footpaths, cycling paths, bridges, public housing, monuments, laying of cables, and other construction work

Green jobs

Creation, restoration, and maintenance of urban commons, green spaces and parks, forested or woody areas, rejuvenation of degraded or waste land, cleaning of water bodies (tanks, rivers, nullahs, lakes) Monitoring and surveying jobs

Gathering, classifying, and storage of information on environmental quality and other aspects of quality of public goods. This will require easy to use equipment for data collection and programmes for data entry

These positions can be for a continuous period of 150 days in a year, and with a different set of people hired each year

Administrative assistance

Assisting municipal offices, local public schools, health centres etc. in administration or other ancillary functions, thereby freeing up the teaching or medical staff for core functions

These positions may also be for a continuous period of 150 days in a year

Care work

Assisting regular public employees working in balwadis or creches, providing child-minding services for parents working longer hours, assisted care for the elderly and various services for differently abled, such as reading to the visually challenged, assisting those with hearing or mobility impairment to manage various activities

Educated youth most hit in employment market, 20% are out of jobs and facing reduced work opportunities

At 6%, India has touched the lowest unemployment rate ever, and the challenge is to create more jobs

Urban unemployment stands at 7.8%, higher as compared to 5.3% unemployment rate in rural areas

India is worse off than US, UK, China, Germany, Canada, France, Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh

Of the over 80 lakh students who graduate per year, only around 10 lakh receive professional degrees

Women are worst affected; they have higher unemployment rates and lower labour force participation rates

More graduates, lesser jobs takes fizz away

HIGH GROWTH RATES AND CHANGE IN ASPIRATIONS

Post 2000, the country has experienced a higher economic growth rate corresponding with a culturally ascendant middle class, with an aspirational lifestyle, therefore petty informal work is less acceptable

THE YOUTH BULGE

India is a very young country, with median age 28, compared to China (37 years) and Western Europe (45 years)

THE EDUCATION WAVE

Workers with no formal education at all are now a mere 12 per cent of the labour force

Enrolment rate for higher education (for those in the 18-23 age group) rose from 11 per cent in 2006 to 26 per cent in 2016

Graduates constituted only 6 per cent of the labour force in 2004, this was up to 15 per cent in 2015 In absolute terms that means nearly 7 crore people

Educated young workforce, no longer concentrated in the large cities, (pre-1991 period). They are now spread across smaller towns and villages THE DOMINANCE OF ‘GENERAL’ DEGREES

Of the 80 lakh students who graduate every year, only around 10 lakh receive professional degrees SUB-

STANDARD DEGREES

Poor quality of education in general and professional streams leading to ‘employability crisis’ or not ‘job-ready’

CASTE

Powerful incentives on part of lower castes to move away from traditional occupations to ensure dignity and respect in society also prevents upper castes from considering any occupations that have a manual component

GENDER

Gender norms prevent women from working in paid employment, actually reduce unemployment numbers because these women remain out of the labour market

With increasing education levels, the number of women, who are not employed and not seeking employment but would work if work was available, is also increasing

Gender norms imposing structural constraints on their mobility, the type of work that they can undertake is restricted. This also contributes to higher unemployment among women than men

(CMIE) and PLFS indicate that unemployment rates are the highest among young, educated, women

COLLAPSE OF PUBLIC SECTOR EMPLOYMENT

The public sector has been a large employer in India when it comes to formal or regular salaried jobs PSUs are also a large employer of general purpose graduates

The slowdown in recruitment and systematic reduction in public sector employment has come at the same time that the supply of educated youth has increased

AUTOMATION

The ability of the private sector to generate employment has been steadily falling across the globe, due to rapid and self-propelling advances in automation

MANUFACTURING SECTOR

In 1980s, one crore rupees of investment created around 80 jobs in the organised manufacturing sector. But, by 2015 this had fallen to less than 10 jobs

The rest are graduates in the Arts, Science or Commerce streams whose education often does not prepare them for work in the modern economy

-News Research Department

Visit news.dtnext.in to explore our interactive epaper!

Download the DT Next app for more exciting features!

Click here for iOS

Click here for Android