CHENNAI: MADRAS was a city of polymaths( ones well versed in many talents), planes were designed by bakers, zoos were built by doctors and clerks ended up being conquerors. Belonging to Denmark, John Goldingham was the first head of the Madras Astronomical Observatory. He was appointed in 1802, and was regarded as one of the prominent polymaths in the city. Although a mathematician, he managed to learn both astronomy and engineering.

Madras was one of the earliest cities to have scientific recording of the climatic conditions. The recording seems to have started in late 1700s, and surprisingly it was started by a British officer as a hobby. William Petrie, an amateur astronomer, started a small private observatory at Egmore, and it was a ramshackle building made with iron rods and timber. Petrie had an assistant called Goldingham, a Danish boy with golden, curly hair. When Petrie retired to England, he gifted all his astronomical and climatic equipment to the East India company. After the first head, Michael Topping, who took the building to the shores of the Cooum on College Road in Nungamabkkam, it was headed by Goldingham.

By then he had his hands full. He had grown to be the government architect and editor of the Government Gazette, apart from serving as first superintendent of the Madras Survey School. This later grew into the Guindy Engineering College and then Anna University. But Nungambakkam observatory gave a good place for his various interests. The observatory was by now a proper building, a single room 40 feet long and 20 feet wide with a 15-foot ceiling. Goldingham’s experimented with measuring the velocity of sound by employing the roar of the fort cannons as a sound source . In 1802, he formulated the Madras time, which was 5 hours and 21 minutes ahead of GMT. Goldingham, thus established the precedent to Indian Standard Time, adopted a century later in 1906. From 1787, observations were made on the eclipses of Jupiter’s satellites, and Goldingham determined the longitude of madras as 80° 18’ 30” based on eclipses of Jupiter’s moons. This was the value used as a benchmark by William Lambton for the Great Trigonometrical Survey.

Goldingham laid a firm foundation for astronomy in Madras and soon after he left, the positions of 11,000 stars on the skies were published in five volumes, which came to be known as the ‘Madras Catalogue’.

Goldingham married Maria Louisa Popham, niece of Admiral Sir Home Riggs Popham, at St. Mary’s in Fort St. George. Popham was the founder of the police force in Madras, and an influential man. Goldingham was a good friend of the governor.

For many years the English elite stayed within the sanctuary of the fort. Their main fear was a swift invasion of the Mysore army under Tipu, which could catch them unawares and outside the fort walls. The victory in the Anglo-Mysore wars caused an exodus to the spaces outside the fort. The governor first moved to a Cooum river side estate, owned by a Portuguese family Medeiros( who, some claim, gave the name to the city itself) this land was bought, and a government house built.

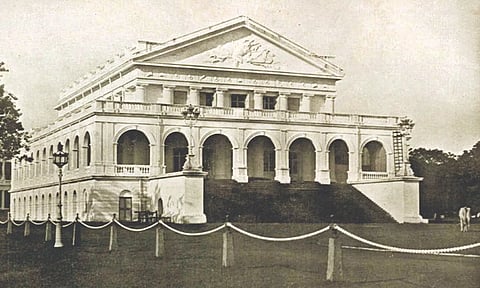

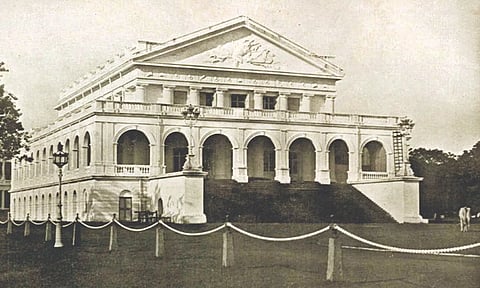

To entertain guests outside the government house, Edward Clive, the governor, commissioned a free-standing banqueting hall.

Clive and Goldingham had an excellent working relationship and so John was entrusted with the job. Instead of a fixed fee he asked for a 15 per cent commission on all expenses related to the building. Then it didn’t seem too much and so the government agreed.

The hall was a work of a genius. Done in Greek style, it resembled the Parthenon in Athens. And so meticulously was it planned with proper engineering drawings for every part of the building, which still survive across museums in the world. The hall was 120 feet long, 65 feet wide and 40 feet tall. It offered excellent views of the river and the island.

In 1802, the hall was opened in a gala function, but the Board of Directors found that Goldingham had drawn 22,500 pagodas as commission, which was far more than a fixed fee. Miffed with this behaviour, they stopped all future payments and sent him back to the observatory. He retired back to England, where he died at Worcester, in July 1849.

Goldingham’s banqueting hall, now renamed as Rajaji hall, has survived all political upheavals, while most of its neighbours have bitten the dust or have been replaced by concrete monstrosities. It hits the headlines whenever a leader passes away and is kept for public homage here.

— The writer is a historian and an author