CHENNAI: Madras was definitely slower than the rest of the country to join the freedom fight. But there were many remarkable events spread around the city that set out to prove the city’s patriotic fervour. From houses to street junctions, and the very Fort where the British power was concentrated, people had their say in demanding independence and self-governance. In this fast-changing urban face of the city, to keep up with its modern status, many of these locations have vanished while many are still evolving.

THE FLAG MAST, FORT ST GEORGE

A mammoth ship had been wrecked on the sea off Madras. While salvaging what they could, the tall teak sail mast was brought back to the Fort. They didn’t know what to do with such an unwieldy piece of timber, but luckily they did not saw it up. Yale, the president of the Fort decided to make it a flag mast for the Fort. The King of England had just given permission to the East India company to sport his colours. The Union Jack was raised on the mast and there it flew for a couple of centuries. The British flag fluttering above the city irritated nationalists. Arya Bashyam, a young artist, climbed up the mast one night, tore it down and unfurled a flag that had been proclaimed as the flag of free India. It’s the same in all aspects to the present flag except that the spinning charka in the white band has been replaced by an Ashoka wheel. Arya was arrested for his audacious act. The original teak flag post has been replaced by a steel pipe now.

PACHAIYAPPAN HALL, CHINA BAZAAR ROAD

A Greek-styled school on China Bazaar Road is perhaps the oldest Indian public building surviving today in Madras. Several meetings were held here, mainly of the Madras Mahajan Sabha protesting British actions like firing on unarmed protestors. However, the building gains importance because of its association with Mahatma Gandhi. Sponsored by the South African Indian associations, Gandhi, a young lawyer, had come to Madras to elucidate the plight of Indians in South Africa. His talk was mediocre and he read out a speech, which bored the audience. But this visit triggered his love for Madras and he would come 14 more times. Each visit had an impact on the man slowly evolving as a Mahatma. The city too, under the impact of his visits, changed its perception of the ruling British and joined the freedom movement with full gusto.

BHARATHI’S HOUSE, TRIPLICANE

Historically, the firebrand Bharathi is found only in George Town where his first stint in Madras was. And also Puducherry claims the lion’s share of his nationalistic poems. But somehow he’s always associated with Triplicane. Bharathi, who had been exiled and arrested on re-entry into British India, settled in Madras. Back in his job as assistant editor in nationalistic daily, Swadesamitran, Bharathi first lived with a Christian pastor in Kilpauk. Then he moved to Thulasinga Perumal Street behind the Parthasarathy Temple on Triplicane. Bharathi didn’t do much nationalistic work here. His job was to translate news and translate Rabindranath Tagore’s poems and short stories into Tamil. But his earlier work in Puducherry had established his political spectrum as a beacon of freedom. His house is maintained as a memorial in Triplicane.

THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY, ADYAR

The East India Company and the British government brought in the maximum number of foreigners into Madras. In addition to that, members of the Theosophical Society brought in many more. They became awed by the power of East Asian religions and abhorred the fact that India was labouring under the chains of European colonialism. Naturally, many had ideas on how India should be justly ruled. The Congress and Theosophical Society had cross membership, and would often adjust the dates of their conferences to allow members to attend both. In fact, the founder of the Congress, Hume, was a theosophist. It was after one such conference in Adyar that theosophists started the Indian National Congress.

SPENCER JUNCTION, MOUNT ROAD

The Spencer junction on Mount Road which has a MGR statue now, was a point of major confrontation between the British and Indian nationalists. James Neil of the Madras Fusiliers Regiment played a major role in putting down the 1857 Sepoy Mutiny. He was killed minutes before the Fusiliers won their greatest victory, but not before he disposed of quite a few Indians in spiteful methods (like blowing them up from a cannon). While celebrated by the imperial government as a martyr, the colonel earned notoriety among Indians and a sobriquet of ‘Butcher of Allahabad’. With the Indian independence movement gaining momentum, the statue, as an emblem of colonial oppression, became an affront. S Satyamurti said that Neil was a “monster in human form whose statue disfigures one of the finest thoroughfares in Madras”. There were many agitations to remove it but the British government did not budge. There was even an attempt by two volunteers to break the statue with an axe and hammer. Finally, when Rajaji formed his government in 1936, he quietly removed the statue first to Ripon building and then the museum where it is now.

GANDHI IRWIN ROAD, EGMORE

The Gandhi-Irwin Pact was a political agreement signed by Mahatma Gandhi and Lord Irwin, Viceroy of India in 1931. Gandhi and Lord Irwin had eight meetings that totalled 24 hours. Although Gandhi was impressed by Irwin’s sincerity, the pact was about a vague offer of ‘dominion status’ for India in an unspecified future and fell far short of Indian expectations. The British were keen to get a closure on the salt march. In return for the discontinuation of the salt march by the Indian National Congress, Gandhi got the release of 90,000 political prisoners. The Madras government felt that much publicity should be given that the two leaders had met over a discussion table. Though there are hundreds of roads across the world named after Mahatma Gandhi, the first was Gandhi Irwin Road in Egmore even when the country was under the British rule.

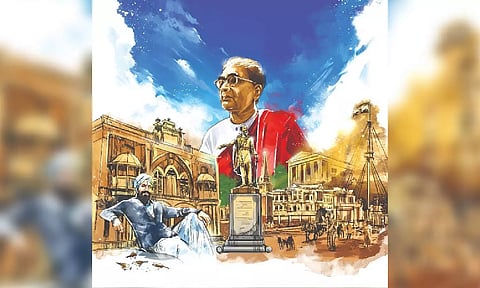

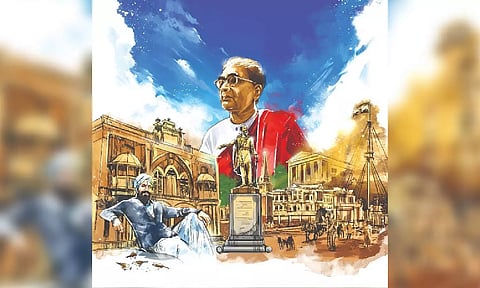

THE LION OF ANDHRA, BROADWAY

Crowds opposing the Simon Commission crowded the Broadway China Bazaar junction. And the British officer commanding the police had orders to stop them from marching to the fort. So he ordered his men to fire without a warning. The unarmed crowd was taken unawares and fled. One protestor lay dead. When a few volunteers offered to walk to the dead man to carry him out, the police gave a warning. “Anyone who touched the dead man would face the same predicament.” There was a stunned silence. Telugu leader Prakasam, a lawyer turned freedom fighter, stepped forward tearing his shirt open, daring the police to shoot him. He walked to the body, lifted it on his shoulder and walked back. From that day, he was called as the Andhra Kesari, and after freedom, the Broadway Street was named after him. The lion of Andhra eventually rose to be the Chief Minister of two states – Madras and Andhra Pradesh.

FORTUNE HOTEL, CATHEDRAL ROAD

Rajaji was living in a bungalow on Cathedral Road and practicing as a lawyer. Gandhi, who used to stay with some friend every time, chose Rajaji’s house as his residence while in Madras. During that trip, Gandhi was quite disturbed because the draconian Rowlatt Act (to subdue agitating Indians) had just been passed. Rowlatt was a non-bailable act allowing indefinite prison stay. It was dawn and Gandhi, restless after a night of disturbed sleep, was hovering between consciousness and sleep. He didn’t know if it was a dream or just an idea that blossomed. Gandhi’s idea of combating the Rowlatt Act was to do an all-India hartal and refuse to co-operate with the government. In a way, this became Gandhi’s most powerful tool to contest an empire which boasted the sun never sets over it. A five-star hotel now stands on the site.

SALT MARCH, MARINA BEACH

The site of many pro-Independence political meetings Gandhi would call it a “quaint little beach”. When Gandhi called out for Indians to make salt on their beaches, illegal that it was in the British empire, there were jokes galore in political circles on the efficacy of the long-awaited agitation. But Gandhi had inspired the nation. People everywhere decided to break the salt tax law. In the Madras presidency, the salt march leader Rajaji decided to shift the agitation to Vedaranyam. Perhaps he was doubtful of the response of Madras, often seen as very loyal to the British. But residents of Madras did not want to be left out of history. In a hurriedly formulated protest, the Telugu residents of Madras organised a salt making campaign in the Marina. Starting with a Telugu song sung by Surya Kumari (later Miss Madras) and Durgabai (Deshmukh), the salt-making commenced. Police firings, lathi charges and other forms of oppression did take a heavy toll.

GOKHALE HALL, ARMENIAN STREET

An Irish woman has the honour of laying the foundation stone of the modern freedom fight in Madras. And most of that activity was in Gokhale Hall on the now crowded Armenian Street. Annie Besant was president of the Theosophical Society. In response to Tilak’s Home Rule Movement, it was in this building that Besant helped launch the Home Rule League to campaign for dominion status for India within the British Empire. She was sure that the British would allow only that as the maximum. She built the Gokhale Hall as a political gym for Madras, and the hall soon transformed into centre of nationalistic activity. Top leaders of the freedom fight lectured here to mammoth crowds. In 1917, she became the first woman president of the organisation and launched her presidency with a series of lectures called ‘Wake up India’. She was promptly arrested and sent to Ooty but managed to squeeze in one of the most well-attended lectures in this hall before that. Gandhi, Nehru and Sarojini Naidu have spoken to spellbound audiences here.