CHENNAI: One of the oldest streets in the black town of Madras is named after a central Asian country. No wonder because the Armenians have contributed immensely to the growth of this city apart from many cities across the world too. For the unversed, there are Armenian streets in at least 50 cities across the world. Even today, Armenians are spread across the world outside Armenia, three times more than within their nation.

This is a painful joke played by history on the landlocked country with its own rich heritage. Sandwiched between empires like the Ottoman Turks and Russia, Armenia was always easily accessible to the invaders. The knowledgeable lot of the Armenians left their motherland to seek their fortunes elsewhere.

Several times, Armenia vanished from the political maps, but the Armenian diaspora added wealth to the cities they settled in.

They came here even before Madras was established. They were a thriving community in the Portuguese Santhome, 100 years before the foundation was laid for Fort St George. When Santhome started shriveling, they moved three miles north. Other Armenians started moving in mainly from Persia and the Philippines.

As their people were spread across countries, this helped them set up a network that could not be rivalled by any other trading power. When the East India company loaded its goods onto a ship for England, the goods would take six months to reach the shores of Britain, crossing the cape of good hope. But a lot of the goods would be sent by the company through the Armenian land network. The list would reach the company headquarters a solid month before the ship with the goods docked. This prior information helped the company to find the best buyer for their goods and increased their profit manifold.

Armenians also lent to the company when there was a shortage of funds. It was their trading and the resultant taxes that enriched the city. Importantly, unlike the Portuguese or the Dutch they had no colonial ambitions and did not offer any competition to the company. Even in trade they carefully kept away the goods the company was dealing in. They were into jade, garnet, diamond and pepper trades.

Soon they started emerging as the richest community in the town. Once, a group of Armenians decided that they would move back to Santhome and revive it as a trade centre. This frightened the company so much that they were given rights, equivalent to the Britishers and were ordered to stay back.

One of the earliest Armenian printing presses was established in Madras in 1772. The first Armenian newspaper was also published here. The publisher- a deep patriot, printed a republican constitution for the Armenian nation when it became free.

The philanthropic nature of the Armenians is what makes their stay in Madras memorable. The most important Armenian citizen, who had a right to own property within the fort was Petrus Uscan. He built the Marmalong( Mambalam) bridge in Saidapet replacing an erstwhile causeway on the Adyar. The bridge has now been replaced though Uscan’s plaque remains. He also paved the steps for St Thomas Mount to enable pilgrims to climb to the church on it easily.

But his help to madras was much bigger than all these munificence. When Marathas or Golconda Sultans wanted to invade Madras, Uscan was sent as an envoy seeking peace and negotiating a truce. The very survival of Madras today may have been due to his negotiation skills.

As time went by, the company lost interest in trading and turned its attention towards conquest and tax farming. Armenians started moving towards greener pastures.

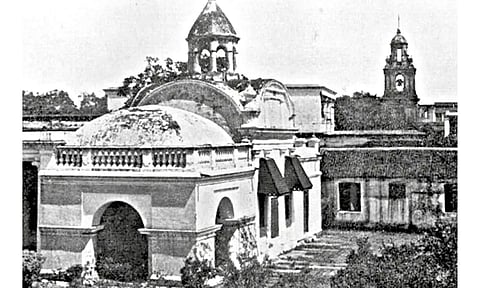

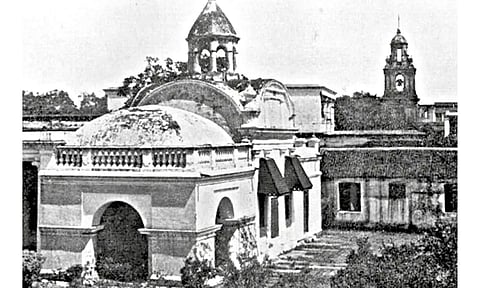

A road leading to the fort was named after the Armenians and their church was built there. 350 burial stones are in the garden of the church. Their separate burial ground was on the island. Because there are only a handful of Armenians today in Chennai, the church is only open for visitors. But every Sunday morning the bells from a three-storied bell tower ring and black town remembers a colourful memory of a tribe which enriched the city.

— The writer is a historian and an author