Chennai

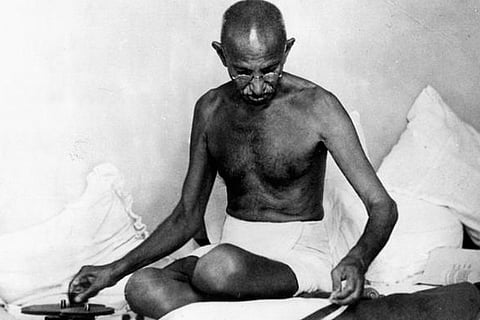

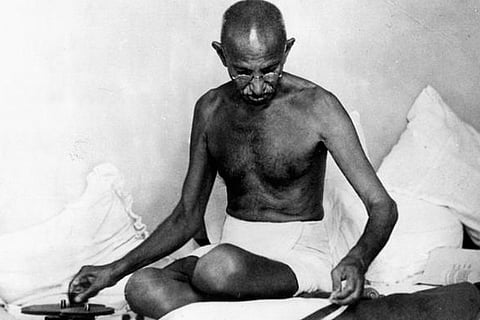

The voyage was a productive one. In just 10 days he penned “Hind Swaraj” on the ship’s stationery. When the book was published in India the following year, the British colonial power banned it as sedition. “It is Swaraj when we learn to rule ourselves,” Gandhi wrote, setting out how Indians could throw off the foreign dominion and create a more equal society. Despite India gaining its independence in 1947, the principles of swaraj set out in Gandhi’s text have never been fully realised. Yet they continue to resonate through Indian civic culture to this day, particularly, says environmentalist Ashish Kothari, in the country’s grassroots environmental movements.

“Swaraj is loosely defined as self-rule but it actually goes much deeper,” says Kothari, who has written extensively on swaraj and the ecological crisis. “It means my own autonomy, self-reliance, self-sufficiency, my independence, both as an individual and as a community. But it’s not the American notion of individualism that I can do what I want.”

Radical democracy

Rather, it is a collective kind of autonomy that recognises our reliance on, and responsibility to, other human beings and other species. As such, living harmoniously with nature is central to swaraj, Kothari says. “One has to be respectful of nature and recognise that other species and Earth as a whole also have rights in their own entity, not just because they’re useful for human beings.” “Eco-swaraj” is not a movement itself, but Kothari uses the term to describe patterns he has observed in hundreds of initiatives across India that are fighting destructive development, such as dams and mining projects, as well as those building sustainable alternatives. In every instance, citizens are the driving force for a bottom-up approach.

“One of the fundamental tenets of eco-swaraj is radical democracy, which means power at the level of ordinary people,” Kothari says. “It’s not about a government laying down policies. It’s really about everybody. Every person in a village builds the capacity to be centrally part of decision making.”

Tenant farm to food sovereignty

That has helped thousands of women in Telangana transform themselves from food seekers to food providers. Before the Indian agricultural NGO Deccan Development Society (DDS) was founded in 1983, many families in the state’s Sangareddy district struggled to get enough to eat. Men and women mostly worked for meagre wages as agricultural laborers on other people’s land, while their own smallholdings lay fallow.

DDS encouraged women to form sanghams, or self-help groups, to discuss food security and come up with solutions. They borrowed seeds from neighboring villages and revived traditional crops suited to the soil and arid climate. The 3,000 women sangham members are now organic farmers, growing up to 35 different crops — such as millet, pulses, oilseeds and wild greens — on every acre of land, and they also have their own seed bank of 80 varieties. During India’s coronavirus lockdown, each member donated 10 kg of millet to cook a nutritious porridge for hundreds of healthcare and sanitation workers.

“Before the sanghams, they were alone, they were individuals,” says Jayasri Cherukuri, co-director of the DDS. “Now, when they are doing things collectively, they get more courage to speak about the issues they are facing.” Cherukuri says women who were afraid to confront their landlords are now demanding a place on local government committees. And it isn’t only rural communities speaking up on decisions that affect their environment. In the city of Bhuj in western Gujarat, residents’ collectives are coming up with their own plans to manage waste and drinking water, which they take to government officials for funding.

— This article has been provided by Deutsche Welle

Visit news.dtnext.in to explore our interactive epaper!

Download the DT Next app for more exciting features!

Click here for iOS

Click here for Android