NEW DELHI: India and Pakistan have seen the scenario play out before: a terror attack in which Indians are killed leads to a succession of escalatory tit-fot-tat measures that put South Asia on the brink of all-out war. And then there is a de-escalation.

The broad contours of that pattern have played out in the most recent crisis, with the latest step being the announcement of a ceasefire on May 10, 2025.

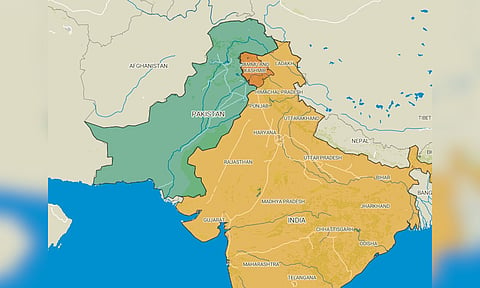

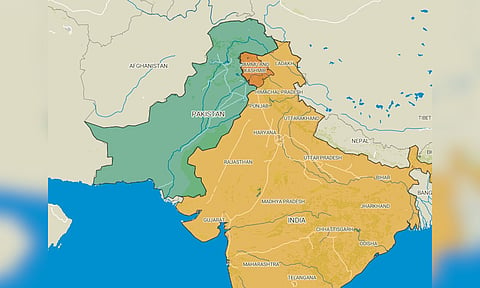

But in another important way, the flare-up – which began on April 22 with a deadly attack in Indian-controlled Kashmir, in which 26 people were killed – represents significant departures from the past. It involved direct missile exchanges targeting sites inside both territories and the use of advanced missile systems and drones by the two nuclear rivals for the first time.

As a scholar of nuclear rivalries, especially between India and Pakistan, I have long been concerned that the erosion of international sovereignty norms, diminished US interest and influence in the region and the stockpiling of advanced military and digital technologies have significantly raised the risk of rapid and uncontrolled escalation in the event of a trigger in South Asia.

These changes have coincided with domestic political shifts in both countries. The pro-Hindu nationalism of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government has heightened communal tensions in the country. Meanwhile Pakistan’s powerful army chief, Gen Syed Asim Munir, has embraced the “two-nation theory,” which holds that Pakistan is a homeland for the subcontinent’s Muslims and India for Hindus.

This religious framing was even seen in the naming of the two countries’ military operations. For India, it is “Operation Sindoor” – a reference to the red vermillion used by married Hindu women, and a provocative nod to the widows of the Kashmir attack. Pakistan called its counter-operation “Bunyan-un-Marsoos” – an Arabic phrase from the Quran meaning “a solid structure.”

The role of Washington

The India-Pakistan rivalry has cost tens of thousands of lives across multiple wars in 1947-48, 1965 and 1971. But since the late 1990s, whenever India and Pakistan approached the brink of war, a familiar de-escalation playbook unfolded: intense diplomacy, often led by the United States, would help defuse tensions.

In 1999, President Bill Clinton’s direct mediation ended the Kargil conflict – a limited war triggered by Pakistani forces crossing the Line of Control into Indian-administered Kashmir – by pressing Pakistan for a withdrawal.

Similarly, after the 2001 attack inside the Indian Parliament by terrorists allegedly linked to Pakistan-based groups Lashkar-e-Taiba and Jaish-e-Mohammed, US Deputy Secretary of State Richard Armitage engaged in intense shuttle diplomacy between Islamabad and New Delhi, averting war.

And after the 2008 Mumbai attacks, which saw 166 people killed by terrorists linked to Lashkar-e-Taiba, rapid and high-level American diplomatic involvement helped restrain India’s response and reduced the risk of an escalating conflict.

As recently as 2019, during the Balakot crisis – which followed a suicide bombing in Pulwama, Kashmir, that killed 40 Indian security personnel – it was American diplomatic pressure that helped contain hostilities. Former Secretary of State Mike Pompeo later wrote in his memoirs, “I do not think the world properly knows just how close the India-Pakistan rivalry came to spilling over into a nuclear conflagration in February 2019.”

A diplomatic void?

Washington as peacemaker made sense: It had influence and a vested interest.

During the Cold War, the US formed a close alliance with Pakistan to counter India’s links with the Soviet Union. And after the 9/11 terror attacks, the US poured tens of billions of dollars in military assistance into Pakistan as a frontline partner in the “war on terror.” Simultaneously, beginning in the early 2000s, the US began cultivating India as a strategic partner.

A stable Pakistan was a crucial partner in the US war in Afghanistan; a friendly India was a strategic counterbalance to China. And this gave the US both the motivation and credibility to act as an effective mediator during moments of India-Pakistan crisis.

Today, however, America’s diplomatic attention has shifted significantly away from South Asia. The process began with the end of the Cold War, but accelerated dramatically after the US withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2021. More recently, the wars in Ukraine and the Middle East have consumed Washington’s diplomatic efforts.

Since President Donald Trump took office in January 2025, the US has not appointed an ambassador in New Delhi or Islamabad, nor confirmed an assistant secretary of state for South and Central Asian Affairs – factors that must have hampered any mediating role for the United States.

And while Trump said the May 10 ceasefire followed a “long night of talks mediated by the United States,” statements from India and Pakistan appeared to downplay US involvement, focusing instead on the direct bilateral nature of negotiations.

Particularly concerning is the nuclear dimension. Pakistan’s nuclear doctrine is that it will use nuclear weapons if its existence is threatened, and it has developed short-range tactical nuclear weapons intended to counter Indian conventional advantages. Meanwhile, India has informally dialed back its historic no-first-use stance, creating ambiguity about its operational doctrine.

Thankfully, as the ceasefire announcement indicates, mediating voices appear to have prevailed this time around. But eroding norms, diminished great power diplomacy and the advent of multi-domain warfare, I argue, made this latest flare-up a dangerous turning point.

What happens next will tell us much about how nuclear rivals manage, or fail to manage, the spiral of conflict in this dangerous new landscape.