By ALEXANDRA JACOBS

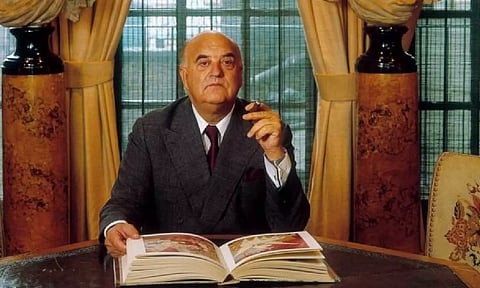

UNITED STATES: Thwarted mega-mergers and private-equity acquisitions, buyouts and layoffs, self-publishing, and artificial intelligence: It’s hard to find a glimmer of glamour in the book business right now. Hold the three-martini lunch, pass the frozen Zoom. Against this tech-inflected landscape, Thomas Harding’s more than serviceable new biography of George Weidenfeld, long a force of letters in England and briefly in the United States, floats as if on stained foolscap. We won’t see the likes of this fellow again is its continual subtext.

Weidenfeld’s most historic move was probably publishing “Lolita” in the United Kingdom in 1959, overcoming strong resistance from the government and the waffling of his business partner, Nigel Nicolson. Started a decade earlier, part of an industry-wide surge of cultured Jewish refugees following World War II, Weidenfeld & Nicolson would assemble a catalog bulging with many of the 20th century’s most important authors: literary novelists, philosophers, scientists, celebrities, democratic leaders. Also — rare among its peers — Mussolini, Hitler and their associates.

“George was the opposite of cancel culture,” the German media mogul Mathias Dopfner, a friend more than 40 years his junior, tells Harding, probably understating the case.

“The Maverick” is an organizational feat: 750,000 pages of company and private papers, winnowed to 19 chapters focusing on significant titles. (The firm, still active, commissioned the book from Harding, a prolific journalist who has written about his own family’s escape from the Holocaust, but did not require final approval.) Weidenfeld lived and worked until he was 96, and difficult choices seem to have been made to keep the book under 300 pages, plus juicier-than-usual endnotes. We get good goss about the tetchy Saul Bellow but not Norman Mailer; Mary McCarthy but not Joan Didion; Mick Jagger, who was “seduced” into writing a memoir for the publisher but couldn’t deliver, but not Keith Richards, who lucratively did.

Though he enjoyed his comforts, Weidenfeld was less motivated by riches than ideas and people. He was a connector, a “convener” and a champion of ideas: defiantly throwing a news conference at the Savoy and advertising James Watson’s “The Double Helix” in movie theaters, for example, after Francis Crick threatened to derail the project.

Weidenfeld was born, with the first name Arthur, to an insurance salesman and a homemaker in Vienna in 1919: a breech baby, left-handed, Jewish and an only child, the last of which, he said in adulthood, was “the most significant fact about my life,” making him a frenetic socializer.

Even more significant, perhaps, was that he escaped the Nazis, after an extraordinary public sword fight with one, part of an initiation rite into a Zionist student fraternity. His parents followed him to London; his grandmothers were not so fortunate. Conversant in several languages and interviewed by the BBC for a job monitoring European radio broadcasts, he told them his interest was history — specifically, “turning points.”