By Bruce Holsinger

NEW YORK: A harrowing passage in Hilary Mantel’s “Wolf Hall” describes the ransacking of Cardinal Wolsey’s house in 1529 by the Dukes of Norfolk and Sussex, a pillage that included recklessly emptying Wolsey’s chests of their medieval books: “The texts are heavy to hold in the arms, and awkward as if they breathed; their pages are made of slunk vellum from stillborn calves, reveined by the illuminator in tints of lapis and leaf-green.”

Though the vellum books are destined “for the king’s libraries,” the marauders treat them roughly, hinting at the irreverent attitude toward medieval manuscripts that characterized much of the early modern period. It seems nothing less than a miracle that so many manuscripts from the era endure to our day. We owe their survival to the ingenuity, labor and passion of those who rescued the books from fires and floods, collected them from the corners of the earth and found ways to preserve them in the face of often daunting obstacles.

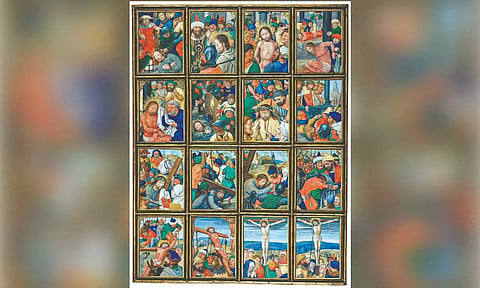

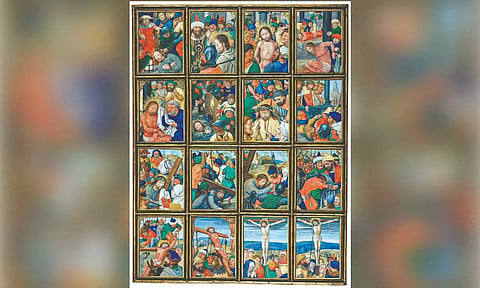

These heroes are the subjects of Christopher de Hamel’s lovingly written and lavishly illustrated “The Manuscripts Club: The People Behind a Thousand Years of Medieval Manuscripts.” Crack the spine of any volume by de Hamel and you will step into a world of bookish wonderment. One of the most eminent living scholars and catalogers of medieval European manuscripts, de Hamel is also their greatest champion, having devoted his career to revealing their treasures and mysteries to scholarly and public audiences alike.

Alongside his catalogs of private and public collections, he has published studies and guidebooks on a variety of topics. “Scribes and Illuminators” (1992) is still widely taught to students in paleography and codicology (the sciences of old handwriting and old manuscript books, respectively), while “The Book: A History of the Bible” (2001) surveys the history of the sacred Hebrew and Christian texts through the lens of their myriad surviving manuscripts.

Here, in a sequel of sorts to his “Meetings With Remarkable Manuscripts” (2017), de Hamel is focused not on the books themselves (though codices and scrolls come in for much expert discussion), but rather on their makers and collectors and preservers, the people who have been responsible for helping to perpetuate one of the great cultural legacies of the pre-modern world.

As the book’s title might suggest, its tone is deliberately clubby. De Hamel imagines a series of intimate conversations between himself and his historical subjects as he roams across centuries, nations and creeds in his pursuit of the larger narrative of preservation. His book tells this story in 12 chapters, each titled after its subject’s particular relation to the manuscripts he or she collected, worshipped from or sometimes faked: “The Bookseller,” “The Illuminator,” “The Librarian,” “The Editor,” “The Forger” and so on. Based on scrupulous research into written sources in numerous languages, the conversations are both informative and informal, as if (to cite just one instance) de Hamel happened to show up on the grounds of an 11th-century monastery for a bookish chat with the willing abbot.