WASHINGTON: Willard Gaylin, a founder of a pioneering research center that wrestled with provocative issues like human behavior, death and dying, personal autonomy and genetics, died on Dec. 30 in Valhalla, N.Y., in Westchester County. He was 97. His daughter Jody Heyward confirmed the death.

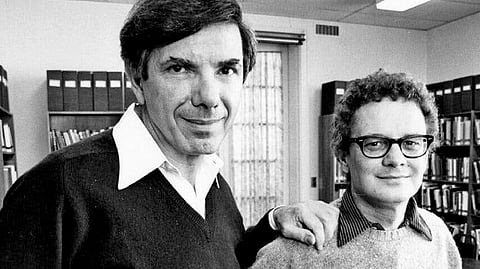

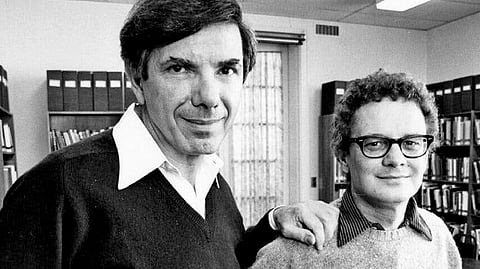

In 1969 Dr. Gaylin, a psychiatrist, and Daniel Callahan started the Hastings Center, devoted to the study of bioethics, in Hastings-on-Hudson, north of New York City. They brought contrasting backgrounds to the venture: Dr. Gaylin was a Jewish psychiatrist and professor; Callahan (who died in 2019) was a leading liberal Roman Catholic thinker who eventually left the church. They also played different roles. Callahan was the center’s operational executive; Dr. Gaylin, who held the title of president for many years, involved himself with various research groups while also maintaining a private practice and writing books.

“He is a fountain of ideas, of imaginative forays into the issues that we are not but should be exploring (ever nagging me on), and of provocative challenges to whatever happens to be the current version of wisdom,” Callahan wrote of Dr. Gaylin in 1994 in The Hastings Center Report, the organization’s bimonthly journal.

Dr. Gaylin brought his psychiatric lens to the center’s exploration of issues like physician-assisted suicide, cloning and the financing of research on human embryonic stem cells. He was also a sounding board for Callahan and the center’s staff.

“He had a polymathic mind, but a playful mind,” Alexander Capron, a bioethicist who was one of the center’s founding fellows, said in a phone interview. “So a young research associate would have a conversation with him and he would throw up a lot of contrarian ideas to make sure they were thinking of those kinds of things. He enriched our thinking through that process.”

Ruth Macklin, who was an associate for behavioral studies at the center, said that Dr. Gaylin’s contribution “was less to the articles we wrote than to our meetings and conferences, where he was a master of oral, colorful language, with wonderful metaphors.” And, she added in a phone interview, “He was such a fast thinker who in his speech often got ahead of himself; a million things were coming to his mind all at once.”

He explored, for example, the ethics of behavior control through brain surgery, electrical stimulation and drugs. Reflecting on the subject, Dr. Gaylin wrote in the center’s journal in 2009: “We attempt to control climate, populations, disease, unemployment and crime, all to general approval, but research that is seen as changing or controlling ‘the nature of our species’ or our behavior and ‘free will’ seems to impose a special threat.”

“With other research,” he added, “we glory in our identification with the scientist. Such scientific pursuit elevates us above, and distinguishes us from, the common animal host. With behavior control, we identify with the research animal as well as the researcher.”

Visit news.dtnext.in to explore our interactive epaper!

Download the DT Next app for more exciting features!

Click here for iOS

Click here for Android