Sometimes the barrier to medical advancement isn’t in the science. It’s the money. In 2003 the first full sequencing of the human genome — “an extensive and highly accurate sequence of the 3.1 billion units of DNA of the human genome,” as The Times put it — was completed; the project had started with a projected cost of roughly $3 billion (the eventual cost was deemed impossible to calculate). Even then, the idea that sequencing could be used to spot and prevent disease was raised — albeit not without skepticism. But with the monumental price of tests, few could afford them.

Over the years, as the underlying technology progressed, the price dropped, but not enough to deliver on the promise of so-called precision medicine, with drugs and treatments tailored to maximise effectiveness for each individual patient. With the price of a partial but useful genome scan hovering around $1,000, scientists believed big breakthroughs would only come when the whole genome sequencing cost sunk to around $100. “One hundred dollars is the kind of money we are looking for,” said Dr. Bruce D. Gelb, a professor of genetics and genomic sciences at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York.

“If someone drops the price of sequencing 10-fold, I can sequence 10 times as many people,” he said. “And you build up your statistical oomph to discover stuff.”

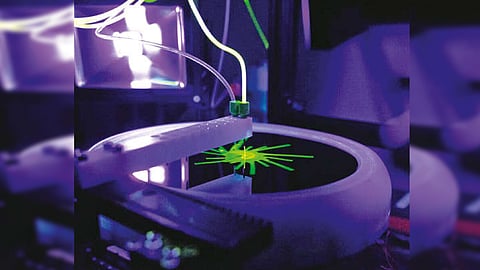

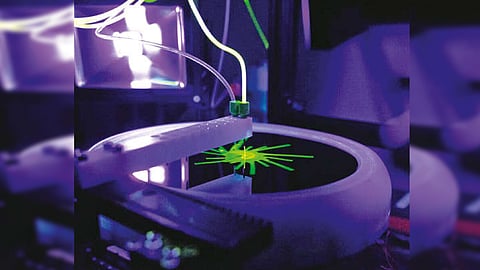

The days of “statistical oomph” — meaning an explosion in the amount of data gleaned from lower-priced tests — appear imminent. Ultima Genomics, a biotech start up, made news at the Advances in Genome Biology and Technology conference in June, unveiling a gene-sequencing machine that it claims can sequence a complete genome for $100.

Whole genome sequencing for that price can potentially accelerate the development of a massive database that can be mined to find genes that cause illnesses, to shed light on the complex influence groups of genes have on one another and to detect genetic changes that indicate the presence of cancer before a PET or M.R.I. scan could.

This intersection of business and science may be as significant to business as it is to science. The sequencing market has so far been dominated by a single company, Illumina, whose patents are running out. And a flood of competitors offering new, comparatively low-cost gene sequencers, each touting its own advantages, is coming — although Ultima is the first company to deliver a $100 sequence.

The company is the brainchild of Gilad Almogy, a California Institute of Technology graduate trained in physics. The idea started percolating for Dr. Almogy after two personal experiences.

One experience involved his work designing machines that inspect computer chips for manufacturing flaws. As chips became more sophisticated, the machines had to quickly scan and evaluate trillions of bits of data. The second experience was eavesdropping as his wife and brother — both doctors — discussed the challenges of diagnosis with their colleagues. The conversations often relied on “asking people, ‘How long have you had the headache? What do you mean? Give me a severity,’” Dr. Almogy recalled. “I just felt that they were data starved,” he added.

Visit news.dtnext.in to explore our interactive epaper!

Download the DT Next app for more exciting features!

Click here for iOS

Click here for Android