The allure of the lurid? Elementary, dear reader

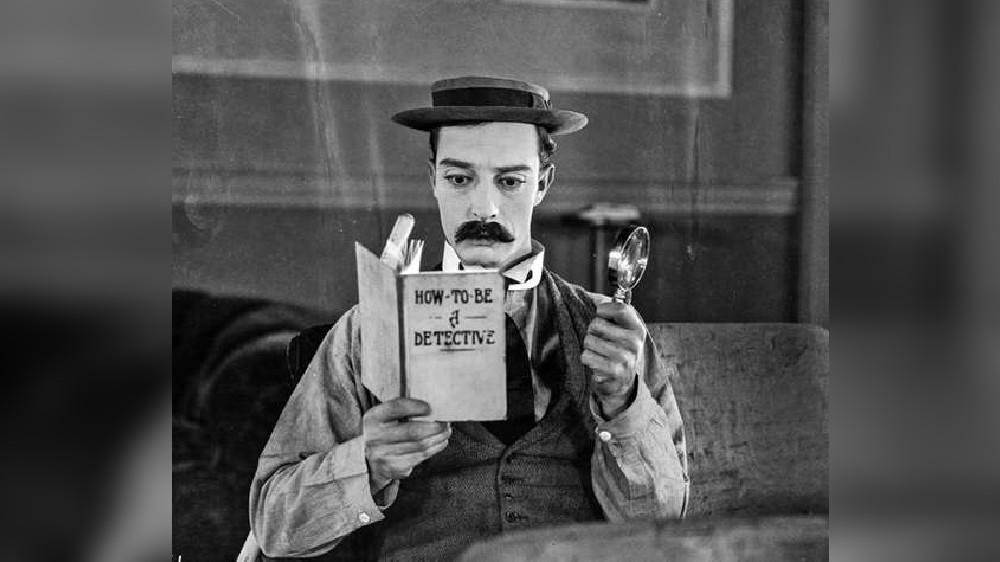

During its so-called Golden Age, in that fragile, frenetic interstice between the world wars, the detective story was a game between writer and reader, a puzzle to be solved through deduction.

In the 1920s, the author (and priest) Ronald Knox came up with what became known as the “Ten Commandments” for writing a mystery. Among them: The character who is the criminal must be mentioned early on; the detective isn’t the culprit, and can’t be helped by accident or unaccountable intuition; only one secret room or passage per story; no supernatural agencies, Chinamen or doubles. These rules made fun of the more outlandish tropes of the genre while also reflecting a particular conception of detective fiction.

During its so-called Golden Age, in that fragile, frenetic interstice between the world wars, the detective story was a game between writer and reader, a puzzle to be solved through deduction. The rules helped ensure fairness — that the writer didn’t “cheat” by, say, murdering a victim via a hitherto undiscovered poison; as Knox might have put it, doing so “not cricket.” But this ideal was short-lived. The horrors of World War II, and the seismic social changes and dislocations that followed, made a mockery of fairness and rationality as guideposts for understanding the modern world.

Martin Edwards charts this shift, and many others, in “The Life of Crime: Detecting the History of Mysteries and Their Creators.” Early on, he sets out his own guide to approaching this informative, entertaining and wide-ranging volume. “This book traces the development of the crime story from its origins to the present day and also explores events that shaped the lives of crime writers and their work,” he writes, adding that he has tried to convey the genre’s “sheer vitality.” A mind-bogglingly prolific author, editor, critic and historian of the genre, Edwards is well-suited to the task.

However altered the world, certain themes that emerged early on in the genre — defined by Edwards as books that focus mainly on “the revelation of the truth about a crime” — have remained constant. One is the perception of crime fiction as not “literary,” and the resulting angst that authors (from Arthur Conan Doyle to Graham Greene to Willard Huntington Wright, who published under the pseudonym S.S. Van Dine to “avoid soiling his good name”) have felt about writing such “entertainments.”

Another is the fidelity with which mysteries reflect the values, desires and anxieties of different eras. The Victorian confidence in science and rationality gave us detectives (most famously Sherlock Holmes) who prevailed through the application of logical reasoning; the hermetically sealed puzzles of the Golden Age, by authors like Agatha Christie and Dorothy Sayers, served as an escape from the devastation of one world war and the fears of another. As the moral righteousness of World War II faded into the ambiguities of the Cold War era, we saw the emergence of spymasters like George Smiley who, in the course of John le Carré’s novels, has to reckon with the rottenness of regimes he has pledged to serve. We meet the cynical, self-destructive noir PI typified by Philip Marlowe, and the amoral antihero (think Tom Ripley).

Edwards writes, knowingly, that “the challenge facing anyone rash enough to write a book about the crime genre as a whole is how to integrate a mass of disparate material into something vaguely coherent.”

Visit news.dtnext.in to explore our interactive epaper!

Download the DT Next app for more exciting features!

Click here for iOS

Click here for Android