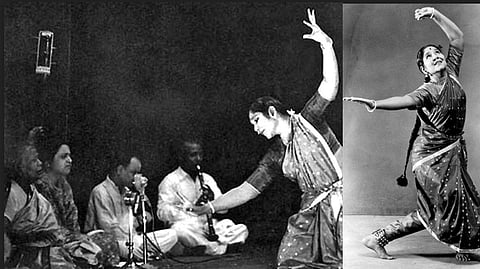

Those were the days: Balasaraswati — The Queen of Abhinaya

CHENNAI: Since time immemorial, the devadasis had pursued vocal classical music and dance as a full time vocation. But there was a huge transition in the traditional temple dance of the Tamils in the 1930s and 1940s. The devadasis of the Isai Vellalar community who held the Sadhirattam in a monopolistic grip were being edged out. Aspersions were being cast on the community on account of moral concerns.

Muthulakshmi Reddy, a social reformer, who was the daughter of a devadasi had spearheaded the anti-nautch (anti-dance) movement in 1927. Lacking political support, they would sit outside the legislature and distribute handbills. They even wrote to lawmakers describing themselves as guardians of dance and music. Two decades later, the Madras Devadasi Act was enacted in October 1947, which gave devadasis the legal right to marry and prohibited the dedication of girls to Hindu temples.

Although they attempted to fight back, history was against them, and the arts they had nurtured for millennia were soon appropriated by other communities. The new proponents, a group of socially influential enthusiasts in Madras had symbolically sanitised the Sathir — removing all elements other than what they thought was morally acceptable to their standards and renamed it as Bharatanatyam. Sathir, which had been an art form that required multidimensional training and which could then be followed as a full time career was set to change. Rukmini Devi Arundale of the Theosophical Society would train for just one year before she performed and it shocked her guru who reportedly left in a huff.

Sathir and Bharatanatyam had possibly overlapped only over a decade — in the 1940s. It was during this historical period when the changeover was happening. Silently waging a war against this transformative lobby was a traditional dancer named Tanjore Balasaraswati (1918–1984), a seventh generation representative of a traditional matrilineal family of musicians and dancers. Her ancestor, Papammal, was a musician and dancer whose patron was the Serfoji court of Thanjavur.

The creative and individual expressions of the Sathir dancer expressed through abhinaya — facial expressions and bodily gestures were ignored in the new dance form, which considered it leaning towards eroticism. Whereas a traditional dancer was supposed to take the audience to a different setting. Bala happened to be a purist. To her, strenuous practice and absolute concentration was the foundation of dance. Real dance should be able to stand tall without props, opulent costumes or distractions on stage.

For two generations, Bala’s family was intimately intertwined with arts, as her mother Jayammal sang and her grandmother Veenai Dhanammal was a veena player. It was a talented family with eight members having taught music and dance internationally and contributing in a big way to the global understanding of the performing arts of India. The house was an artistic hub with concerts held on Fridays and Sundays.

As a toddler, Bala was inspired by a beggar who would dance in front of her house for alms. The child started imitating his actions and she would forever recognise him as her first guru recalling that it was a siddha who had come to awaken her. She also grew up seeing the performances of Mylapore Gauri Ammal — one of the popular dancers of that time. However, traditional Sathir was facing a sociocultural backlash and when the toddler Bala expressed her interest in dancing, she was initially discouraged. But soon people began recognising her inherent talent and permitted her to learn to dance.

In 1925, at age seven, Bala had her arangetram at Kancheepuram and left the audience captivated. She would go on to learn Carnatic music as well, but she never performed. She knew dance was multidimensional and that a knowledge in several disciplines was essential to impress the learned audience. Bala would sing for her daughter Lakshmi Knight’s dance recitals only much later.

As a teenager, she was seen by renowned choreographer Uday Shankar, who decided to promote her across the country. Performing in Calcutta in 1934 at the All Bengal Music Conference, Bala danced to the tune of Jana Gana Mana, a decade before it was chosen as the national anthem. And that was in the presence of Rabindranath Tagore. Rukmini Devi Arundale would invite her to dance in 1933 in the Theosophical Society. At that time, neither knew they would end up as bitter rivals.

Bala was a very creative dancer. She would dance to the same song a dozen times and no performance would be alike. Every muscle in the face strived in unison to express a feeling or a story.

Abhinaya was a deeply individualised expression and depended on the interpretative skill of the artist. The value of abhinaya was lost when audiences grew larger and none beyond the first few rows could catch the expressions. Sans abhinaya, traditionalists said the Bharatanatyam industry churns out dancers like an assembly line.

So intense was Bala’s mastery over the grammar of abhinaya leading to her extempore innovations on stage that a fascinated Satyajit Ray would make a full documentary on her, capturing in close angle all her intricate expressions.

Much recognition came to Bala only in her late 40s. She gave scintillating performances in Europe and the US. She performed in Madras Music academy continuously for nearly three decades and taught at its school on campus. She decided to share her knowledge and learning from “Balamma” was an important supplement in a dancer’s life. Not only for the incredible art she possessed, but for being a dancer and an artiste at a time of crisis, Balasaraswati remains a historical and cultural milestone.

Reference: Balasaraswati: Her Art and Life by Douglas M Knight Jr

Visit news.dtnext.in to explore our interactive epaper!

Download the DT Next app for more exciting features!

Click here for iOS

Click here for Android