CHENNAI: To those not well versed in police parlance, ‘bandobust’ is a technical term used to denote the planning and deployment of men, mobiles and arms to handle a major assemblage of policemen and mobiles for managing law and order, and crime situations during festivals, elections, major strikes in industries and establishments like railways or state transports etc. In brief, it means police arrangements to maintain public order and control crimes.

The Madurai Chithirai festival, the Kumbakonam Mahamaham festival, the Vinayagar Chaturthi processions, the Velankanni festival and elections are some occasions when such bandobusts are ordered in the police department.

It was the last week of April 1983. I, the Assistant Superintendent of Police, Virudhachalam, received a curt wireless order from my Superintendent of Police, “Proceed to Dindigul with two inspectors, 40 sub-inspectors, 400 men, 40 muskets and 400 ball ammunition for bye-election duties“.

The election referred to in the order was the historical election of May 1973, in which MG Ramachandran tested the popularity of his nascent party and trounced the powerful ruling party from which he broke away hardly eight months ago. The election was a keenly contested, acrimonious, violent and vituperative affair with determined cadres of both camps, vying with their rivals adopting all trickeries of elections. Dindigul suffered a glut of visits from numerous campaigning VIPs, national and local, innumerable noisy public meetings, traffic-disturbing processions, vociferous demonstrations etc. Besides all these, it had hordes of paideia cadres descended from all over the State mainly to intimidate the rivals, bamboozle the police, and affect law and order... Dindigul was boiling.

For a youngster like me, fresh from the academy, an order to move to such an action-filled Dindigul, commanding a heavy contingent of men and officers was an exciting experience, that I devotedly wished for... I resolved that I should make a success of myself in this venture and show my superiors what I am capable of!

Unlike now, in the seventies, the department was quite short of vehicles. Policemen used to move from place to place for bandobusts not in groups in buses as now, but individually taking bus warrants and rail warrants carrying their personal effects, arms, lathis and shields to the derision of co-passengers on trains and contempt of conductors in buses. These unorganised and independent marches were not only cumbersome to men and officers but also used to invariably result in delayed reporting for duties, resulting in pulling up, skirmishes between officers and men, consequent punishments etc.

I thought I should put an end to this custom of independent movement of men and officers and move to Dindigul en bloc under my direct command and report sharply at the scheduled time. So, instead of directing men and officers to report at Dindigul individually, I ordered them to report at Cuddalore, the district headquarters, so that I could verify the number, their fitness, their uniform, and keep them under the command of sub-inspectors. I could hear the murmur of men and officers about my novel order as their freedom to travel and report as they liked had been scuttled. Yet, having no other option, they assembled at Cuddalore.

The election referred to in the order was the historical election of May 1973, in which MG Ramachandran tested the popularity of his nascent party and trounced the powerful ruling party from which he broke away hardly eight months ago

I divided the assembled men into 40 teams under 40 sub-inspectors and went to the bus warrant clerk to get warrants to procure bus tickets. The clerk dropped a bombshell. He said he wouldn’t be able to issue warrants as the District Police office had heavy outstanding to be paid to bus companies and there was little likelihood of companies honouring our warrants. I started entertaining doubts about whether I had taken the right decision in assembling all.

The good clerk, however, suggested that I might try rail warrants. The clerk in charge of rail warrants, who was very sympathetic to my predicament, readily issued two warrants — a first-class one to me and inspectors, and a second-class warrant for the rest.

Much relieved, clasping the warrants, I rushed to the Station Master, Cuddalore OT, and requested him to accommodate all of us on one train. The seasoned Station Master listened to my fervent plea for accommodation en bloc but expressed his inability as he had other regular passengers to provide for and suggested splitting the strength and providing in two trains. But I was reluctant to this proposal as it defeated my novel desire of moving them as one contingent. I pleaded with the Station Master again to help me out. Appreciating my steely resolve, and unwilling to scuttle a young man’s initiative, he suggested that I could perhaps try hiring an exclusive train at a little extra cost.

I rushed back to the District Superintendent of Police and placed the proposal of the Station Master. He spoke to someone in the chief office in Madras, and ordered me to go ahead. My joy knew no bounds. I went to the Station Master and informed him.

The inspector counted the men repeatedly and hesitatingly reported: “Two missing”. I was worried as well as annoyed; worried as I imagined they might have fallen asleep on the train, annoyed because they have thwarted my attempts to fashion a new mode of movement en bloc BY EVENING, I WAS INFORMED THAT A TRAIN HAD BEEN KEPT AT MY DISPOSAL. PICTURES THAT I HAD SEEN IN THE WAR BOOKS THAT DEPICTED THE MOVEMENT OF SOLDIERS DURING WORLD WARS FILLED MY MIND. I WENT TO THE LAYBY, TOOK A TRAIN EXAMINER, AND EXAMINED THE CARRIAGES, BULBS, FANS, WATER, LOCKS OF DOORS ETC. OF THE COACHES ALLOTTED

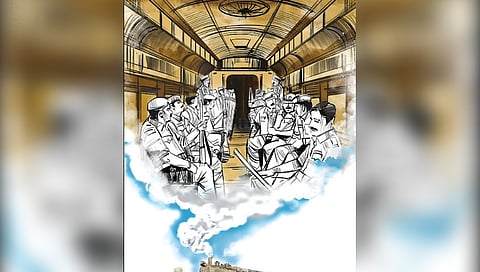

By evening, I was informed that a train had been kept at my disposal. Pictures that I had seen in the war books that depicted the movement of soldiers during World Wars filled my mind. I went to the layby, took a train examiner, and examined the carriages, bulbs, fans, water, locks of doors etc. of the coaches allotted.

The carriages allotted were of World War vintage — wooden coaches meant for soldiers’ movement, with doors openable as in cars these days, wooden benches, which when lifted would show up rifle racks underneath. The engine to haul was a coalfired one with a long smoke-emitting chimney. The first class in which I had to travel had a cosy sofa and bed with a good shower and water closet. I was thrilled.

I instructed my men and officers to be in uniform in the allotted coaches and not to get down anywhere without permission of their sub-inspectors in charge. I also told them that they should be in uniform while getting down at Dindigul.

The train, we travelled in, gave way to all the routine trains and goods trains en route and reached Dindigul the next morning. I got down from the train and asked the senior inspector to report whether we had brought the strength intact. The inspector counted the men repeatedly and hesitatingly reported: “Two missing”. I was worried as well as annoyed; worried as I imagined they might have fallen asleep on the train, annoyed because they have defied my orders and thwarted my attempts to fashion a new mode of movement of men for bandobust and earn a good name.

As I was standing wringing my hands, ruminating about the fate of the missing, a constable stepped out of the ranks, saluted and informed me that he saw two getting out of the coach to drink water at Mayavaram. Another constable added that I need not worry as they definitely would join us as they had their sisters’ house in Mayavaram and they probably had broken their journey for that reason. I chided the in-charges for their slack control.

Leaving the men in ranks, I rang up the office of the Superintendent of Police, Dindigul to announce our arrival and ask for vehicles to move to our place of duty. The stock reply that I got for my repeated request was that vehicles would soon come, but the “soon“did not materialise at all. The experienced constables told me that it would not so easily come. Someone in the rank fell out, saluted me and said last time when they came for a bandobust of this kind, they stayed on the dilapidated premises opposite to the railway station and suggested that we might move there. The rank and file took the cue, broke discipline, crossed the railway tracks and moved to the premises. I was dismayed but what to do? I followed them. The vehicles did not come at all.

The camp we moved in was full of dirt, dust and cobwebs. But the policemen were resourceful. They procured broomsticks and water from nowhere, within a few minutes, cleaned the premises and made themselves and me comfortable. They spread themselves on the ground and procured for me two rope cots, one for my luggage and the other for my rest.

I was called for a meeting by the local Superintendent. In the meeting hall, I met a number of veterans on special duty. I had to deploy my men in 40 locations in Ambathurai police limits and maintain law and order and ensure a smooth election. That was the duty assigned.

I deployed my men and officers in different locations and moved around inspecting their comfort, discipline and performance, every day. As I was on such regular patrol one day, I heard over wireless that Inspector-General Arul was coming by road from Madurai to Dindigul to review bandobust. Those days there was only One Inspector-General and they were rarely seen by field officers. I thought I should make it known to him that I was managing law and order in Ambathurai and its surroundings.

So, I wore a well-pressed uniform and waited on the road to greet the Inspector General as he drove past my station. The impressive Impala he travelled in passed by as I tendered a crisp, sharp salute. The Inspector General noticed me, pulled his car to a screeching halt and got it reversed towards me. I felt that I had gained his attention. I ran to the station to alert the staff.

He came into the station and queried: “You are...?”

In my desire to impress, I rattled off: “I am ASP, Virudhachalam. I have brought two Inspectors, 40 sub-inspectors, 400 men, 40 muskets and 400 ball ammunition.”

The Inspector General queried: “Where are they billeted...?” I gave the details of disposition rapidly.

He did not stop but asked me further: “When did you visit them?”

I replied that I visited every morning and evening. He questioned: “How many are on the sick list?”

I replied: “None”. He said “good” and questioned further: “Is there sufficient water? Is there electricity on the camping premises?”

These questions, I always remembered when I went for a review of major bandobusts later in my life.

The culmination of the searching examination by the Inspector General was his sudden query to the DIG Madurai Range Thiru. K Chenthamarai, who stood a step behind. “Chentha, how about posting this youngster at Dindigul after the elections?” He, in his gruff voice, replied: “Post him, sir, I will groom him.”

Dindigul was one of the prized postings for ASP, as it was semi-urban, had a big bungalow, and compact jurisdiction with Sirumalai just opposite to the bungalow, and Kodaikanal not far off.

I was posted to Dindigul as ASP within four days of the election result.

When I received the order, the thought that came to my mind was what my ustad in Mount Abu, told me: “It is officers who build officers, not politicians”, a truism to be remembered by the present breed.

Visit news.dtnext.in to explore our interactive epaper!

Download the DT Next app for more exciting features!

Click here for iOS

Click here for Android