Chennai

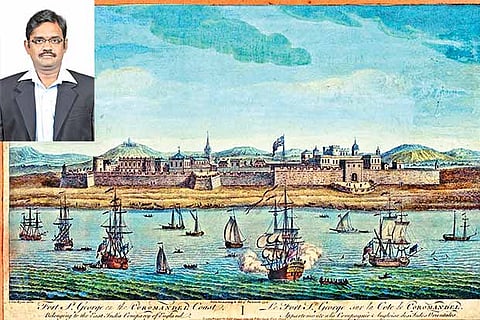

Very few cities in the world have their birthday celebrated. Madras had a bash on August 22, the date of acquisition of a three-square mile sandy stretch on the northern banks of a yet-to-be-named river that joined the bay. The lessee was the East India Company, then a fledgling commercial enterprise whose toehold in Madras would lead it to becoming perhaps the richest entity in the then world, one that had kings, tsars and emperors. The lessor was technically the Vijayanagar empire, once the lighthouse of Hindu rule in south India, but by then confined to a shadow of its old glory.

No doubt Madras has had pre-colonial habitations mentioned in the Roman times, temples mentioned in the Devaram and even the cavemen settlements of pre-homo sapiens species dotting its map. A fresh unearthing of a Vijayanagar edict mentions a place called Madarasapattinam in the same spot. Why then should a city be rejoicing in its recent colonial past, ask sceptics.

The British were the last of the colonial powers to set shop on the Coromandel coast. Tranquebar and Santhome predate Madras by at least a century. The duo of Andrew Cogan and Francis Day and their Indian gunpowder maker Nagabattan were responsible for the choice.

But Madras was not the ideal place for a factory or fort in any way. There was a sand bar in the adjoining sea, which annoyed the navy and commercial ships as it effectively forbade the approach of ships. The security of Fort St George was rather precarious and its residents seldom knew what fate awaited them before another day had dawned. The Governor’s mansion was built at an angle to deflect cannon balls, while the height of buildings within the fort was restricted so as to not to provide things for the enemy to aim at.

Mysore Sultan Hyder Ali was among those who cast greedy glances on the fort. Hyder tried throwing in carcasses of animals in the water supply to the fort, trying to use thirst as a weapon to bring it down to its knees. Maratha king Shivaji, too, wanted to take over the city. But placated by the gifts the East India Company (EIC) showered on him, he galloped towards Senji instead.

But Joseph-François Dupleix, the governor general of French territories in India, was a more serious threat. He was very keen to take Madras, having seen its prosperity from close quarters from Pondicherry. His wife Begum Dupleix (as the locals called her), a half-Portuguese who had Mylapore links, urged him on to capture it.

French sepoys had crept almost all the way to the walls of the fort, undetected, because of the Black Town that surrounded the fort like a vice. The fort fell and the cream of the British society was carted away in chains to Pondicherry and held for ransom. A few of them scaled the walls of the fort, waded across the Poonamallee river (Cooum) and walked all the way to Fort St David in Cuddalore some 200 km away.

Less than a year later, a disciplined armed force was formed called the Madras Regiment, which is often considered the parent of the armies of the countries of India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. Even as the British were weighing their options, fate came to their aid. A seemingly unconnected Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1748, whereby Maria Theresa was confirmed as Archduchess of Austria, was marked by the mutual restitution of conquests by European powers. Madras was exchanged for an island in Nova Scotia, Canada.

The French sulked but the British back home celebrated the return of Madras with firecrackers. The French did try to take Madras again. But the British had strengthened the forts and cleared the Black Town, creating an esplanade for good view all around, which enabled them to sustain the siege period in relative comfort. Soon, the French power slowly petered down and became concentrated only in a few enclaves sustained by the forbearance of the British.

Madras as a city had a fighting spirit, with the fear of invasion served to bind the small community more firmly together. While we have heard of the cruelties meted by the EIC, we cannot ignore the fact that some of the Company officials were extraordinary rulers.

Francis Whyte Ellis was well-regarded for his translation of Tirukkural, identification of the Dravidian languages, and his great interest in ensuring people had vaccination; Munroe for his work on Ryotwari systems, for reforming temple organisations and the impact on Tirupati and Mantralayam. And men like Arthur Cotton or John Pennycuick for damming the raging rivers and enriching vast tracts of land (and are still considered as demigods in those districts).

Technology, too, grew under the British. The first plane in Asia (four years after the Wright brothers’ invention hit the skies), the first car in India and the first railway track (with bullocks pulling the wagons) were all in Madras. The women, too, had their spot under the sun, securing admission to medical colleges ahead of many other countries, and voting in elections before most of their sisters elsewhere in the world. With a Municipal Corporation set-up, and medical, agriculture and engineering colleges, Madras developed as a well administered city of the learned. Talent flocked in droves to the pattinam.

The British, on their part, treated Madras with great regard. To say it was the seed from which the British empire bloomed is not too high a praise to bestow upon Madras. In return, Madras, too, was more grateful than the rest of the country to the British, especially during the Sepoy mutiny. Its soldiers were used to suppress the mutinies, defeat the kings. People professed loyalty to the company, and then to the British empire later. Competitions were held, even in Carnatic music circles, to write verse in tribute to the emperor king and gold coins were offered as prize. Freedom movements, especially Quit India, were lacklustre here compared to the rest of the country.

History cannot be partisan, it should not have opinions. Its duty is to report the past with the least interjection of personal wants and wishes.

What happened in the bygone days in this geographical area will encompass cavemen details, history of the Tamil kings and their temple villages like Mylapore and Triplicane, and the Vijayanagar rule. But Madras as a town that we live in and love has not originated from these villages that the city gobbled in its hunger for expansion. What we see today is a natural progression of a colonial town that Andrew Cogan and Francis Day established 380 years ago. Colonial Madras is the core of the city’s past and we cannot deny it. Happy Madras Month!

—The author is a historian

Visit news.dtnext.in to explore our interactive epaper!

Download the DT Next app for more exciting features!

Click here for iOS

Click here for Android