Chennai

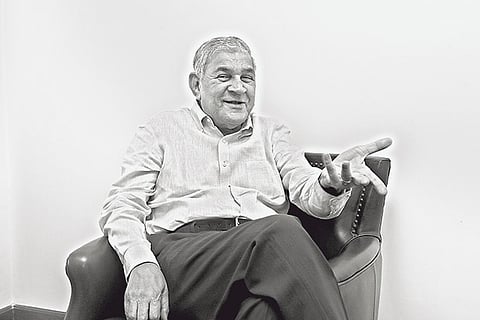

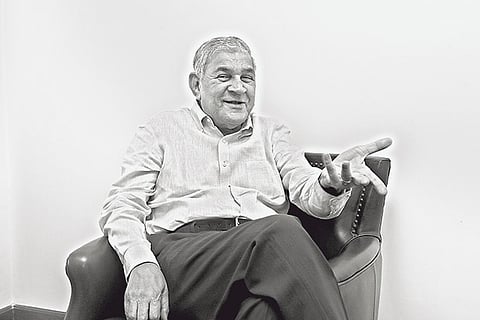

Seeded in 1966 as a small enterprise, SFL has had to surmount challenges of a protectionist regime to emerge as a thriving conglomerate in a liberalised era. Today, SFL is an iconic company, that recently turned 50, and is exploring new horizons. DT Next caught up with Suresh Krishna, the doyen of manufacturing, who presently leads a semi-retired life.

In the 60s, Krishna used to punch in 11-hour shifts at the factory in Ambattur industrial estate, burning the midnight oil for about a decade. Likening work-life balance to an idiom, the literature graduate-turned business baron says he is as comfortable with his work schedule now as he was then.

“In retrospect, I wish I had spent more at home. But then, if I had, the energy I would have expended at the factory would have been less. How it would have affected the company’s growth is anybody’s guess,” he recalls.

Scaling up business operations

The shifting of the factory to Padi led to the forming of a professional team – to handle works, quality, accounts and sales, among others. He then could plan family time taking the opportunity to travel across India.

“I cut down nightly visits to once a week, spent more evenings at home. We took our children for vacations to a different state every year. It was a fantastic education for our children and we ourselves discovered a lot by that time,” notes Krishna, who adds that by the time his two daughters, after finishing college, went to America, SFL had transformed into a fairly well-established entity.

Settling down to this schedule for five decades now, the Padmashri awardee says, “I am sort of semi-retired now. My two daughters Arathi and Arundhati have taken over, I come to office for about 3-4 hours in the morning… but those 3-hours I am reasonably busy.” The hands that built SFL are now involved in giving vital inputs to sustain the growth momentum of SFL’s journey that began five decades ago.

Hurdles abound

“Moving from Ambattur industrial estate to Padi was daunting as we were a small-scale business going largescale. In 1977, the entire factory was flooded as the Ambattur lake was also overflowing. Coming from the TVS group, ours was an undertaking governed by the Monopolies and Restrictive Trade Practices Act. I did not belong to the ‘A’ category of auto components as manufacturing of bolts and nuts was categorised under hardware. I wanted to expand my capacity from 2,400 tonnes annually (now we are about 90,000 tonnes). But, the government said we couldn’t expand unless we opted to go public by 49 pc.”

Krishna laments, “We did not need the money and we didn’t want to go public. Either we expanded or our customers went elsewhere. So reluctantly, I went public in 1982 for which I have never forgiven the government. I was so hurt by the Centre’s socialistic view of society, how I should work and share my wealth.”

When he cited the example of all the other companies in the manufacturing sector, the response he got was they were all ‘A’ category firms whereas SFL was only making ‘C’ category items. Left with no other choice, SFL went public, divesting 49 per cent of its stake. However, that didn’t deter him. “When General Motors came and talked to us whether we would like to become sole supplier of radiator caps, we didn’t know anything about it. GM said they would give the entire plant to us, teach us how to do it as they wanted to put that plant here. So, that became a turning point for SFL,” recounts the businessman.

“The other big change in my life happened in 1987-88 when I became the CII President,” he says, as he points to the visibility that he achieved during the Rajiv Gandhi era, when from a cocooned business environ, Krishna became a national figure. Besides interacting with politicos and industrialists, he lectured on quality, exports and competitiveness prior to liberalisation, as the emphasis was to turn India into a globally-competitive nation and not rely on tariff barriers.

SFL later took the decision to shed its sole reliance on nuts and bolts. “We had to create more pillars on which the company could stand,” he says, as he draws the genesis of the multiple pillars of SFL such as cold extrusion, exports, transmission in SEZ. “Nuts and bolts contribute only about 35 to 40 per cent of the business now and the balance comes from outside,” says Krishna.

Business then and now

“Post-liberalisation in 1991, we were still not completely liberalised. Today, it is not so. We do not have to go to the government for anything. I have not been to Delhi for 20 years on a bureaucratic visit now. But this also means more imports. Firms like Mercedes Benz could import from wherever they wanted and not rely on domestic suppliers. In my time, they could have bought only from me. So, there was a sense of balance. On one hand, you had to compete with international suppliers. On the other hand, you had the protection regime. If I were 40 years younger, I would prefer today’s milieu with its total freedom,” he remarks.

Leveraging competence

“International buyers today are well disposed towards India more than they were back in the day. We never came across as an industrial superpower. With the arrival of MNCs like Nissan, Mercedes and Skoda and the success story of Suzuki, people realised there was engineering talent here. Local purchasing offices of these MNCs are keen to buy from India. That is why the automotive industry has boomed in the last ten years,” he points out.

Incidentally, SFL’s China factory, set up about 11 years ago, is doing well. “It is one of the rare Indian manufacturing companies to have presence in China; the Chinese don’t import from India, as they would rather support their own companies. But they consider us a Chinese company and not an MNC. We have invested a lot – 250 workers, mostly Chinese with only a handful of Indians,” says Krishna.

Keeping pace with the times, SFL has also been exploring sunrise sectors. Aerospace is one such, which Krishna likens this way: “The manufacturers are extremely cautious in buying anything to do with aerospace and we have made headway here.”

Way forward

India’s automobile industry should do 10 million cars and around 50-60 million motorcycles. But, now there is disruption, which must be managed. Are we going the whole hog with electric vehicles or remain with ICE (internal combustion engines)? There are many pros: it is cleaner and the drivability of e-vehicles is far superior in terms of maneuverability, transmission and torque. Plus it’s powered by solar energy. By 2030, only 2.3 per cent of the cars will be electric, while the most optimistic say it will be 23 pc. Even assuming 30 or 40 pc out of 84 million, go the e-way, enough cars will run on ICE, into which a lot of investment has been made. There is also this googly about autonomous cars replacing today’s models. So, the next 20-30 years is going to be very challenging. SFL has done a lot of work around e-vehicles. Our products are peripheral. You will still need bolts and nuts and 70 per cent of our company will remain unaffected.

Visit news.dtnext.in to explore our interactive epaper!

Download the DT Next app for more exciting features!

Click here for iOS

Click here for Android