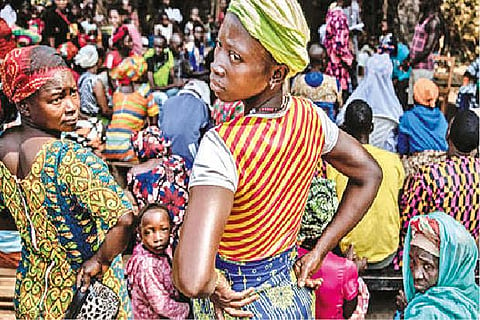

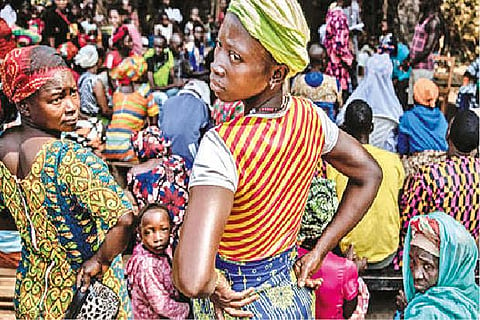

There are no COVID fears here. The district’s COVID-19 response center has registered just 11 cases since the start of the pandemic, and no deaths. At the regional hospital, the wards are packed — with malaria patients. The door to the COVID isolation ward is bolted shut and overgrown with weeds. People cram together for weddings, matches, concerts, with no masks in sight. Sierra Leone, a nation of 8 mn on the coast of Western Africa, feels like a land inexplicably spared as a plague passed overhead. What has happened — or hasn’t happened — here and in much of sub-Saharan Africa is a mystery of the pandemic.

The low rate of coronavirus infections, hospitalisations and deaths in West and Central Africa is the focus of a debate that has divided scientists on the continent and beyond. Have the sick or dead simply not been counted? If COVID has in fact done less damage here, why is that? If it has been just as vicious, how have we missed it? The answers “are relevant not just to us, but have implications for the greater public good,” said Austin Demby, Sierra Leone’s health minister, in an interview in Freetown, the capital. The assertion that COVID isn’t as big a threat in Africa has sparked debate about whether the African Union’s push to vaccinate 70% of Africans against the virus this year is the best use of health care resources, given that the devastation from other pathogens, such as malaria, appears to be much higher.

In the first months of the pandemic, there was fear that COVID might eviscerate Africa, tearing through countries with health systems as weak as Sierra Leone’s, where there are just three doctors for every 100,000 people, according to the World Health Organization. The high prevalence of malaria, HIV, tuberculosis and malnutrition was seen as kindling for disaster.

That has not happened. The first iteration of the virus that raced around the world had comparatively minimal impact here. The beta variant ravaged South Africa, as did delta and omicron, yet much of the rest of the continent did not record similar death tolls. Into Year Three of the pandemic, new research shows there is no longer any question of whether COVID has spread widely in Africa. It has. Studies that tested blood samples for antibodies to SARS-CoV-2, the official name for the virus that causes COVID, show that about two-thirds of the population in most sub-Saharan countries do indeed have those antibodies. Since only 14% of the population has received any kind of COVID vaccination, the antibodies are overwhelmingly from infection.

A new WHO-led analysis, not yet peer-reviewed, synthesised surveys from across the continent and found that 65% of Africans had been infected by the third quarter of 2021, higher than the rate in many parts of the world. Just 4% of Africans had been vaccinated when these data were gathered. So the virus is in Africa. Is it killing fewer people? Some speculation has focused on the relative youth of Africans. Their median age is 19 years, compared with 43 in Europe and 38 in the United States. Nearly two-thirds of the population in sub-Saharan Africa is under 25, and only 3% is 65 or older. That means far fewer people, comparatively, have lived long enough to develop the health issues (cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic respiratory disease and cancer) that can sharply increase the risk of severe disease and death from COVID. Young people infected by the coronavirus are often asymptomatic, which could account for the low number of reported cases.

Plenty of other hypotheses have been floated. High temperatures and the fact that much of life is spent outdoors could be preventing spread. Or the low population density in many areas, or limited public transportation infrastructure. Perhaps exposure to other pathogens, including coronaviruses and deadly infections such as Lassa fever and Ebola, has somehow offered protection.

Visit news.dtnext.in to explore our interactive epaper!

Download the DT Next app for more exciting features!

Click here for iOS

Click here for Android