Chennai

Joan Didion had migraines, excruciating ones, which descended on her as often as once a week, leaving her “almost unconscious with pain” and forcing her to shut down and shut out the world until, like a terrifying storm, they passed. We’re aware of the details because she insisted that we be. She laid them out in an essay published in 1968, making certain that we understood her vulnerability. In another essay, she clued us into how innocent she was when she arrived in Manhattan in her 20s and how jaded she was when, years later, she returned to California, “the Golden State,” which she appraised through a filter not of sunshine but of dread. The Santa Ana winds were always in the offing. The earth could quake at any moment.

And in yet another essay, she confessed the strains and uncertainty of her marriage. “I am sitting in a high-ceilinged room in the Royal Hawaiian Hotel in Honolulu watching the long translucent curtains billow in the trade wind and trying to put my life back together,” she reported. Her husband, John Gregory Dunne, was with her. “I avoid his eyes,” she wrote. “We are here on this island in the middle of the Pacific in lieu of filing for divorce.”

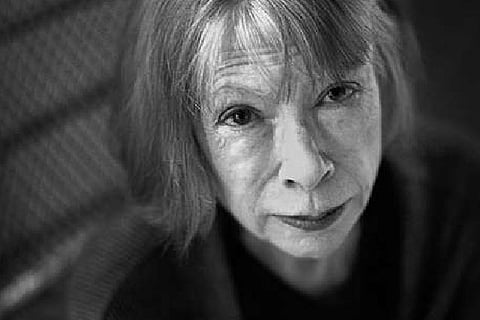

Didion, who died on Thursday, at the age of 87, from complications related to Parkinson’s disease, was a model and trailblazer in many ways. She belonged, in some measure, to the school of New Journalism, which integrated techniques associated with fiction into non-fiction. She had an eye for detail that was a kind of X-ray vision. She had an ear for absurdity no less acute. And her sentences — dear Lord, her sentences! She was, as I noted in a tribute to her in 2017, a sorceress of syntax, with a cadence to her words and a music to her paragraphs that were utterly spellbinding.

But she also stood out — and had enormous impact — for something else: She conceded her subjectivity. Traced her blind spots. Showed her hand. Instead of mimicking the swagger and voice-of-God authority that many other journalists affected, she stipulated — sometimes as the very subject of an essay, other times in its margins — to what a peculiar narrator she could be. She catalogued her own oddities, and she did so not as an exercise in narcissism but as an act of candour.

In the news business over recent years, there has been significant discussion about whether any one writer can be wholly objective and neutral, whether it’s wise to assert (or, perhaps, pretend) as much, whether the idea that a particular account could have been produced in its exact form by any number of different reporters is patently false on its face. Some outlets now give their audiences more information about the people bringing them the news or permit those journalists to create profiles on social media that are a kind of piecemeal, steadily accruing autobiography. That’s not intended as a surrender to subjectivity. It’s meant as transparency.

Well, Didion was there long ago. Her signature essays from the 1960s and 1970s — which, for the true Didion cultist, mattered infinitely more than her novels or than anything else until her grief memoir, “The Year of Magical Thinking,” in 2005 — were radically transparent. That’s not to say that she didn’t selectively edit the aspects of her life that she presented for public consumption, hold on to secrets, turn herself into a character of her choosing. Every writer does that. Every human does that.

But Didion had the boldness and brilliance to realise, ahead of her time, that she bolstered her credibility and cemented her bond with readers if she volunteered that her sensibilities invariably steered her in certain directions and circumscribed her observations. So she owned up to her prejudices and parameters. She copped to her leanings and limits.

In that dispatch from Hawaii, after mentioning the prospect of divorce, she added: “I tell you this not as aimless revelation but because I want you to know, as you read me, precisely who I am and where I am and what is on my mind. I want you to understand exactly what you are getting: You are getting a woman who for some time now has felt radically separated from most of the ideas that seem to interest other people. You are getting a woman who somewhere along the line misplaced whatever slight faith she ever had in the social contract, in the meliorative principle, in the whole grand pattern of human endeavor.”

That essay appears in “The White Album,” a collection that was published in 1979. Another collection, “Slouching Towards Bethlehem,” was published in 1968, and in the preface to it, she delineated characteristics that made her ill suited for journalism. She was “bad at interviewing people,” she wrote. She didn’t like making telephone calls.

“My only advantage as a reporter,” she continued, “is that I am so physically small, so temperamentally unobtrusive and so neurotically inarticulate that people tend to forget that my presence runs counter to their best interests. And it always does. That is one last thing to remember: Writers are always selling somebody out.”

She gave her readers notice of that and, in other essays, of her disinclination to find patterns where she was supposed to and of her estrangement from the idealism and protests of the very decade that she was most famous for covering. “If I could believe that going to a barricade would affect man’s fate in the slightest I would go to that barricade, and quite often I wish that I could, but it would be less than honest to say that I expect to happen upon such a happy ending,” she wrote in the essay “On the Morning After the Sixties,” which appears in “The White Album.” She was saying that she was an imperfect witness. Which, of course, made her a perfect one.

Just hours before I got the news that Didion had died, I had typed her name into my laptop. I was constructing the syllabus for a course in first-person writing that I’ll be teaching at Duke University this spring, so I was compiling material for my students to read. Two of Didion’s essays from “Slouching Towards Bethlehem” — “Goodbye to All That” and “On Self-Respect” — were my first and second items on that list.

That’s because they’re gorgeous, with phrases and flourishes that represent the highest level of prose. It’s because they demonstrate the manner in which a writer can universalise the personal, wringing a collective moral from an individual experience.

But it’s also because of how she pokes fun — and even gapes — at herself, encouraging readers not so much to follow her lead as to marvel at how lost she can get. It’s a cunning invitation. Didion grasped something essential about not just journalism but life: The most trustworthy and likable guides are the ones who occasionally ask others for directions.

Frank Bruni is a professor of public policy at Duke University, and a contributing Opinion writer with NYT©2021

The New York Times

Visit news.dtnext.in to explore our interactive epaper!

Download the DT Next app for more exciting features!

Click here for iOS

Click here for Android