Chennai

For a long time, the archaeological evidence — from Egypt, Mesopotamia, China, Mesoamerica and elsewhere — did appear to confirm this. If you put enough people in one place, the evidence seemed to show, they would start dividing themselves into social classes. You could see inequality emerge in the archaeological record with the appearance of temples and palaces, presided over by rulers and their elite kinsmen, and storehouses and workshops, run by administrators and overseers. Civilisation seemed to come as a package: It meant misery and suffering for those who would inevitably be reduced to serfs, slaves or debtors, but it also allowed for the possibility of art, technology, and science.

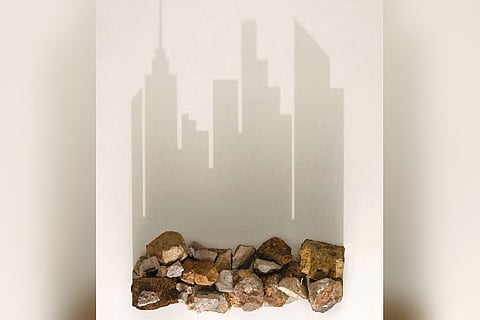

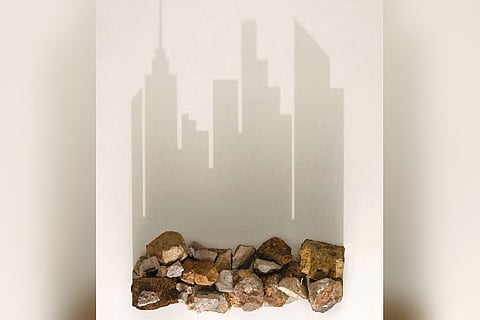

That makes wistful pessimism about the human condition seem like common sense: Yes, living in a truly egalitarian society might be possible if you’re a Pygmy or a Kalahari Bushman. But if you want to live in a city like New York, London or Shanghai — if you want all the good things that come with concentrations of people and resources — then you have to accept the bad things, too. For generations, such assumptions have formed part of our origin story. The history we learn in school has made us more willing to tolerate a world in which some can turn their wealth into power over others, while others are told their needs are not important and their lives have no intrinsic worth. As a result, we are more likely to believe that inequality is just an inescapable consequence of living in large, complex, urban, technologically sophisticated societies.

We want to offer an entirely different account of human history. We believe that much of what has been discovered in the last few decades, by archaeologists and others in kindred disciplines, cuts against the conventional wisdom propounded by modern “big history” writers. What this new evidence shows is that a surprising number of the world’s earliest cities were organised along robustly egalitarian lines. In some regions, we now know, urban populations governed themselves for centuries without any indication of the temples and palaces that would later emerge; in others, temples and palaces never emerged at all, and there is simply no evidence of a class of administrators or any other sort of ruling stratum. It would seem that the mere fact of urban life does not, necessarily, imply any particular form of political organisation, and never did. Far from resigning us to inequality, the new picture that is now emerging of humanity’s deep past may open our eyes to egalitarian possibilities we otherwise would have never considered.

Wherever cities emerged, they defined a new phase of world history. Settlements inhabited by tens of thousands of people made their first appearance around 6,000 years ago. The conventional story goes that cities developed largely because of advances in technology: They were a result of the agricultural revolution, which set off a chain of developments that made it possible to support large numbers of people living in one place. But in fact, one of the most populous early cities appeared not in Eurasia — with its many technical and logistical advantages — but in Mesoamerica, which had no wheeled vehicles or sailing ships, no animal-powered transport and much less in the way of metallurgy or literate bureaucracy. In short, it’s easy to overstate the importance of new technologies in setting the overall direction of change.

Almost everywhere, in these early cities, we find grand, self-conscious statements of civic unity, the arrangement of built spaces in harmonious and often beautiful patterns, clearly reflecting some kind of planning at the municipal scale. Where we do have written sources (ancient Mesopotamia, for example), we find large groups of citizens referring to themselves simply as “the people” of a given city (or often its “sons”), united by devotion to its founding ancestors, its gods or heroes, its civic infrastructure and ritual calendar. In China’s Shandong Province, urban settlements were present over a thousand years before the earliest known royal dynasties, and similar findings have emerged from the Maya lowlands, where ceremonial centers of truly enormous size — so far, presenting no evidence of monarchy or stratification — can now be dated back as far as 1000 B.C., long before the rise of Classic Maya kings and dynasties.

What held these early experiments in urbanisation together, if not kings, soldiers, and bureaucrats? For answers, we might turn to some other surprising discoveries on the interior grasslands of eastern Europe, north of the Black Sea, where archaeologists have found cities, just as large and ancient as those of Mesopotamia. The earliest date back to around 4100 B.C. While Mesopotamian cities, in what are now the lands of Syria and Iraq, took form initially around temples, and later also royal palaces, the prehistoric cities of Ukraine and Moldova were startling experiments in decentralised urbanisation. These sites were planned on the image of a great circle — or series of circles — of houses, with nobody first, nobody last, divided into districts with assembly buildings for public meetings.

If it all sounds a little drab or “simple,” we should bear in mind the ecology of these early Ukrainian cities. Living at the frontier of forest and steppe, the residents were not just cereal farmers and livestock-keepers, but also hunted deer and wild boar, imported salt, flint and copper, and kept gardens within the bounds of the city, consuming apples, pears, cherries, acorns, hazelnuts and apricots — all served on painted ceramics, which are considered among the finest aesthetic creations of the prehistoric world.

But the point remains: Why do we assume that people who have figured out a way for a large population to govern and support itself without temples, palaces and military fortifications — that is, without overt displays of arrogance and cruelty — are somehow less complex than those who have not? Why would we hesitate to dignify such a place with the name of “city”? The mega-sites of Ukraine and adjoining regions were inhabited from roughly 4100 to 3300 B.C., which is a considerably longer period of time than most subsequent urban settlements. Eventually, they were abandoned. We still don’t know why. What they offer us, in the meantime, is significant: further proof that a highly egalitarian society has been possible on an urban scale.

Graeber and Wengrow are the authors of the forthcoming book, “The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity,” from which this essay is adapted.

The New York Times

Visit news.dtnext.in to explore our interactive epaper!

Download the DT Next app for more exciting features!

Click here for iOS

Click here for Android