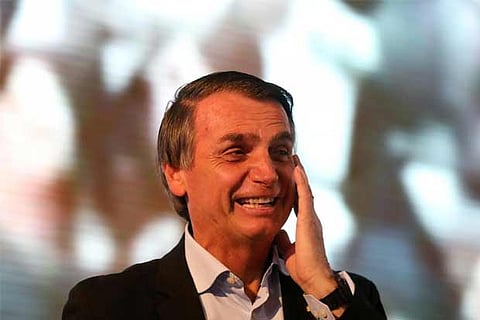

Why Brazil's business elites are warming to a far-right flamethrower for president

The nation’s currency and equity markets have increasingly rallied in lock-step with favorable poll numbers for Bolsonaro, a firebrand congressman better known for his broadsides against gays and Afro-Brazilians than his embrace of free markets. Over a 27-year legislative career, Bolsonaro has voted repeatedly to preserve state-owned monopolies and against reforming Brazil’s bloated public pension system.

But his selection of a respected University of Chicago-educated banker, Paulo Guedes, as his economic advisor is good enough for many investors and business owners. Some view Bolsonaro as the least worst alternative in a race that is shaping up as a showdown between the far right and far left.

Pollsters are predicting a second-round run-off between Bolsonaro and former Sao Paulo Mayor Fernando Haddad, candidate for the leftist Workers Party, or PT, who has been surging in the polls. Many economists blame statist policies of the PT, which ruled Brazil for much of the past 15 years, for tipping Brazil into a deep downturn, whose vestiges are still weighing on the economy.

Luciano Hang, the owner of the privately-owned department store chain Havan, is one of few executives to openly support Bolsonaro, whose unabashed admiration for Brazil’s former military dictatorship and frequent denigration of women and minorities have alienated large swaths of the electorate.

Still, Hang estimates that “more than 80 percent” of people in a 300-member business council to which he belongs are backing Bolsonaro now that more moderate candidates in a crowded presidential field appear to be fading.

“Business people and entrepreneurs throughout Brazil in all segments of the public favor Bolsonaro and will actively campaign for him,” Hang said.

Bolsonaro’s growing acceptance among Brazil’s business elites underscores how a polarized political landscape is driving moderates to extremes, and how markets are unsettled by a wide-open and unpredictable race. Those jitters have already slowed the country’s M&A and IPO markets to a crawl and last month sent Brazil’s currency, the real, to a record low against the dollar.

Bolsonaro is the current front-runner among 13 presidential candidates heading into the first round of balloting slated for Oct. 7, with 27 percent of the likely vote, according to a survey last week from polling firm Ibope.

But whether he ultimately prevails remains to be seen. If no candidate wins a majority on the first ballot, as is predicted, the top two vote-getters will face off in a final round of voting on Oct. 28, when the same poll shows Bolsonaro losing to Haddad by 4 percentage points.

Haddad, an economist, has been meeting with major investors to quell fears about a PT return to power. Known for his bookish, calm demeanor, Haddad has played up his orthodox positions on inflation, exchange rates and deficits.

Still, he has acknowledged he would dump the labor and spending reforms of unpopular outgoing President Michel Temer. And he has made it clear his administration would run state-controlled oil company Petroleo Brasileiro SA or Petrobras as a development vehicle and scuttle the proposed sale of Embraer’s commercial jet business to Boeing Co.

Haddad recently tweeted that the market was “an abstract entity that terrorizes the public.”

SUPER MINISTER

Corporate admirers of Bolsonaro, meanwhile, point to his choice of advisor Guedes as a reason to tune out their candidate’s divisive rhetoric, authoritarian leanings and wildly shifting views on Brazil’s economy. Bolsonaro, for example, once suggested that ex-President Fernando Henrique Cardoso be gunned down for privatizing former government enterprises including iron ore miner Vale.

In contrast, Guedes, currently the head of asset management firm Bozano Investimentos, is a fierce advocate of privatizing Petrobras and government-controlled lender Banco do Brasil SA.

If elected, Bolsonaro has promised to make Guedes a kind of super minister in charge of finance, planning and trade, with wide latitude to set economic policy.

Guedes has held a series of meetings with investment banks, corporate chieftains and international investors to coax them onto the Bolsonaro bandwagon. The banker has also met with members of the Finance Ministry at least three times in an effort to signal continuity with Temer’s reform agenda, including changes to the country’s insolvent pension system.

“Paulo Guedes indeed gives Bolsonaro’s candidacy a lot of credibility,” said Claudio Pacini, head of Brazilian stock trading at U.S. broker INTL FCStone in Miami. “Together with the fear of the rise of the left, the two things mitigate in Bolsonaro’s favor.”

SHAKY ALLIANCE?

But some question how long the Bolsonaro-Guedes partnership might last even if the candidate is elected.

“Bolsonaro is a recent convert to pro-market liberalism - that’s not his thing, it’s never been his thing,” said Monica de Bolle, director of Latin American studies at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS) in Washington.

Such doubts were heightened last month when Guedes proposed reviving an unpopular financial transactions tax known as the CPMF to raise badly needed revenue. That idea was swiftly shot down by Bolsonaro from the hospital where he has been convalescing. He was stabbed by a mentally disturbed assailant at a campaign rally last month.

Guedes canceled at least two planned public appearances soon after, fueling speculation that he had been effectively muzzled by the campaign for the time being.

Guedes declined to comment about the disagreement. But de Bolle of SAIS sees turbulence ahead.

“It seems obvious that Paulo Guedes wouldn’t last in a Bolsonaro government,” she said.

Many also wonder how effectively Bolsonaro might govern if elected. In nearly three decades in Congress, he has not authored a single significant piece of legislation. His Social Liberty Party, the ninth party to which he has belonged, has only a smattering of votes in Brazil’s legislature. He would need to forge alliances with other parties to get anything done, a task at which he has little experience.

“The government is broke and Bolsonaro has no allies to push for budget cuts, and not even a history of pursuing them,” said a senior banker at one of Brazil’s top lenders.

For the business community, the banker said, a vote for Bolsonaro is a choice between “the awful and the extremely awful.”

Visit news.dtnext.in to explore our interactive epaper!

Download the DT Next app for more exciting features!

Click here for iOS

Click here for Android