Chennai

For many years, villagers are often forced to travel to the nearest district headquarters even for small cases relating to farm boundaries, right to use canal irrigation and verbal fights.

The objective of Gram Nyayalayas Act, recommended by the Law Commission is to deliver justice to rural people in a quick and easy manner. It was passed in 2008 and implemented on October 2, 2009. UNDP (United Nations Development Program) gave Rs 44.60 crore as aid to this program between 2009 and 2017. But till date, it has not been effectively implemented and not many are aware of its existence. The Act provides for the setting up of 5,000 courts in rural areas in the first phase and allotted Rs 1,400 crore for this project. So far, only 200 rural courts have been established.

Funds allotment

Central government allotment per rural court is Rs 18 lakh, of which Rs 10 lakh is for the court building, Rs 5 lakh for vehicles and Rs 3 lakh for furniture and fittings. It will function with one judge, one head clerk and one staff member. State governments will pay their salaries. The judge should be paid the salary equivalent to a first class judicial magistrate.

Implementation of the Act

Only 11 states in India have implemented this Act. States such as Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Karnataka, Kerala, Odisha, Jharkhand, Punjab, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan and Goa have implemented this Act so far. Eighteen states including Tamil Nadu are yet to implement it and this remains a concern.

Social activists lament that even among the states which have implemented this Act, except for Kerala, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh, others have not implemented it properly. In some areas, small court buildings have been built. In a few other places, arrangement of mobile courts with judges visiting twice a week has been made. But judges visit only once or twice a month!

Reasons for the delay

Constraint of funds is citied as the major reason. But state governments and government officials remain indifferent. Lawyers oppose this in many areas; even boycotting courts in protest in some areas, arguing that in villages, chances of casteist forces and people with political clout interfering in the judicial process is high.

But social activists say lawyers oppose this Act because it enables people to argue on their own, without lawyers. Finding honest judges who will deliver justice to the common man without succumbing to any pressure is considered a major challenge because more than half of the current district level judges face various accusations.

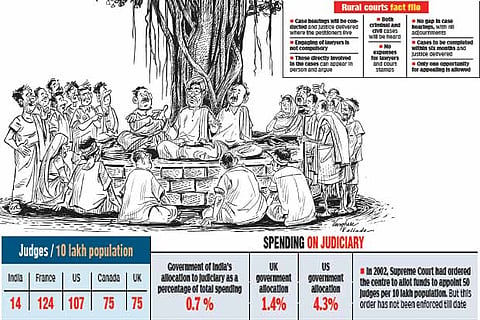

As on date, there is a vacancy of 38 per cent in the High Courts. In the lower judiciary nearly 5,000 vacancies exist. Both central and state governments do not allot sufficient funds for the judiciary. Even today some of the courts lack basic infrastructure and necessities. Hence, nearly 43.5 lakh cases are pending in high courts. Even in the fast track courts, which were set up to deliver speedy justice, nearly six lakh cases remain pending.

Mahatma Gandhi’s dream

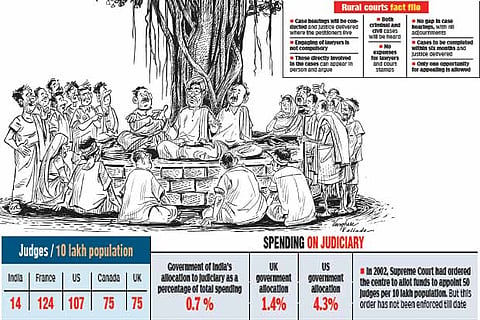

That our villages should become self-governing and function as self-supporting entities, was the dream of the father of the nation, Mahatma Gandhi. In the olden days, all village issues were settled within the boundaries of the village by the village elders concerned, who heard the cases.

It had its own merits and demerits like unbiased judgements and others based on caste discrimination. Hence the system holding village courts under the trees was ended and the Indian Constitution was enforced. But this had made the delivery of justice to rural people very difficult to attain.

According to Praveen Patel, leader, National Federation of Societies for Fast Justice, nearly 140 of our social organisations are continuously pressurising the central and state governments to establish village courts. “We have formed a federation of social organisations for speedy justice for this purpose.”

He said, “We filed a case in the Supreme Court through Prasanth Bhushan! As a result, the Supreme Court has sent notice to the central and state governments seeking their replies. We have also petitioned the Telangana governor. He had forwarded that to the Chief Justice of India. He had ordered the chief secretary to establish village courts quickly.”

“We have submitted a petition to the Chhattisgarh Chief Minister. He has directed us to represent to the Union minister for Law. But union minister Ravi Shankar Prasad had sent back the petition saying that the state government is empowered to take a decision. Nothing further happened. On the whole, there is apathy from all sides on this issue!,” he says.

“While the government order to establish commercial courts was released on December 31, 2015, it was given a retrospective effect from October 2015, meaning that it had to be implemented immediately. This Act is very helpful to corporate companies. But at the same time, why are the village courts not established even after 11 years,” he asks.

S Ramesh, coordinator, The Tamil Nadu Association for Speedy Justice, the state unit of the federation, says, “When we asked the state government about the status of village courts in the state through an RTI, we got the response that the government has not taken any effort in this regard”.

Send your comments to: NRD.thanthi@dt.co.in

News Research Department

Visit news.dtnext.in to explore our interactive epaper!

Download the DT Next app for more exciting features!

Click here for iOS

Click here for Android