Chennai

The committee recommended continuation of the three-language formula (Regional language, Hindi and English) in schools. The committee also advocated multi-lingualism and flexibility in schools to equip students to face the competitive world better.

When the draft was made public for feedback and suggestion last week, all political parties in Tamil Nadu were up in arms and issued statements warning the Centre of dire consequences if Hindi was imposed on them. Protests came from West Bengal, Karnataka and Punjab too. Quick to respond, the Central government revised the draft as, “in keeping with the principle of flexibility, students who wish to change one or more of the three languages they are studying may do so in Grade 6 or Grade 7, so long as they are able to still demonstrate proficiency in three languages...”

In the first version of the report, there was a paragraph that led to some confusion and was interpreted as imposing Hindi learning on non-Hindi speaking states. To clear this confusion, the government has put out a revised version which reflects thoughts more clearly.

Unlike other states, Tamil Nadu has had a long history of opposing moves to make learning Hindi compulsory in the state’s schools.

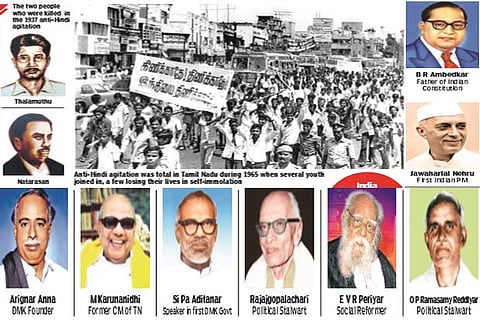

1937 First Hindi agitation

The first such agitation was launched in 1937, when C Rajagopalachari, who was the then Premier of Madras Presidency (which comprised portions of Kerala, Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh apart from Tamil Nadu) introduced Hindi learning for students of Class 6, 7 and 8 in 125 schools as a pilot project.

The move was vehemently opposed in Tamil speaking areas, where common people including women, children and youth took to the streets voicing their concern against the move and courted arrest. Two people – Thalamuthu and Natarasan – were killed in the agitation. Rajaji struggled to manage the agitation, which continued for two years. Later, the state constructed a memorial building in Egmore, and named it the Thalamuthu-Natarasan building which currently houses the CMDA office. Why are Tamils so opposed to learning Hindi? The Tamil language and literature has a rich legacy and stands on its own whereas other Indian languages are in one way or the other associated with Sanskrit language. The cold war between those speaking these different languages is quite visible. In those days, Sanskrit mixed Tamil language was prevalent. For example ‘mozhi’ (language) in Tamil was also called as ‘baashai’, which is a derivative from Sanskrit.

The same way ‘thuni’ (clothes) in Tamil was also called ‘vasthram’, a Sanskrit derivative. ‘Thanneer’ (water) was also called ‘jalam’, again a Sanskrit derivative. ‘Sambhashanai’ for Tamil word ‘uraiyadal’ (dialogue) and ‘upadhyay’ for ‘asiriyar’ (teacher), was also used.

Also in temples, Sanskrit slokas were chanted instead of Tamil scriptures Thevaram, Thiruvasagam, Nalayirathivyaprabandham and Andal songs. It upset Tamil scholars and Saivites. They all considered Hindi as an offshoot of Sanskrit. Hence, stalwarts like E V Ramasamy Naicker, Maraimalai Adigal, Thiru Vi Ka, Somasundara Bharathiar, K A P Viswanatham and Bharathidasan headed vigorous anti-Hindi agitations.

Karunanidhi led agitation at 14

In 1938, M Karunanidhi, at the age of 14, gathered a band of boys and took to the streets of Tiruvarur shouting slogans against imposition of Hindi. Whenever the Central government planned to impose Hindi, the first voice to oppose the move was of Karunanidhi’s. He was leading the anti-Hindi agitation at its peak. Even after coming to power, he never budged to Central government pressure and was stern on the issue. After Anna, it was Karunanidhi who kept the spirit of anti-Hindi agitation alive and it forced MGR and Jayalalithaa, who came to power after him, to follow suit.

In 1948, O P Ramasamy Reddiyar, who was the chief minister of the then Madras Presidency, decided to introduce Hindi in schools as an optional language. He had to withdraw his decision following widespread opposition from all quarters.

After Independence, a majority of national leaders including Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, Vallabhai Patel, Rajaji and B R Ambedkar unanimously wanted to drop English and make the language of the land that unites Indians - Hindi, as the official language.

Principal architect of the Constitution of India, Ambedkar recommended that Hindi be the national language and did not like the idea of reorganisation of states based on language since he feared that there were chances of political parties using it as a weapon in future. But Rajaji and TT Krishnamachari did not accept the idea of discarding English totally and making Hindi the only official language. Following this, the matter was referred to Munshi Iyengar-led team which gave a grace period of 15 years to let English be the joint official language and then make Hindi the official language to enable non-Hindi speaking states to pick up proficiency in Hindi.

1963 Third anti-Hindi agitation

In 1963, C N Annadurai, who was then a Rajya Sabha member, requested Prime Minister Nehru not to impose Hindi as an official language in non-Hindi speaking states and let English continue. Members of Parliament from north India strongly opposed this. They said 15 years was too long a period and it was time Hindi was made the official language.

In response, Krishnamachari asked, “Do you want a united India or only a Hindi-speaking India?” Following this fight, Congress ministers C Subramaniam and O V Alagesan submitted their resignation in protest against the move to make Hindi as the only official language.

Then AICC president K Kamaraj, West Bengal Congress leader Atulya Ghosh, the then chief ministers, Nijalingappa (Karnataka) and Neelam Sanjiva Reddy (Andhra Pradesh) too opined that the move would encourage separatism and discrimination of the non-Hindi speaking people.

Nehru’s assurance

Following the tough stance taken by non-Hindi speaking states, then prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru assured in Parliament that English may continue till the non-Hindi speaking states accept Hindi as official language and Hindi would never be imposed on them until then.

But Anna did not agree to this either, insisting that the word ‘may’ must be removed and instead the word ‘should’ should be used in Nehru's assurance in Parliament. Despite several rounds of arguments between Anna and Nehru that the assurance must be rephrased as: “English should continue as an official language.....”, Nehru never agreed to this. Nehru’s argument was that there is not much difference between the word may and should and told Anna, not to worry about it. It was his assurance that Hindi will never be imposed on Tamil Nadu and other non-Hindi speaking states.

Rajaji who had changed his views on Hindi being made the only official language also wrote several letters to Nehru from 1958 onwards and even during 1964 requesting and pleading with Nehru not to impose Hindi. Rajaji said “Never to impose Hindi ever and English should be an official language for ever”.

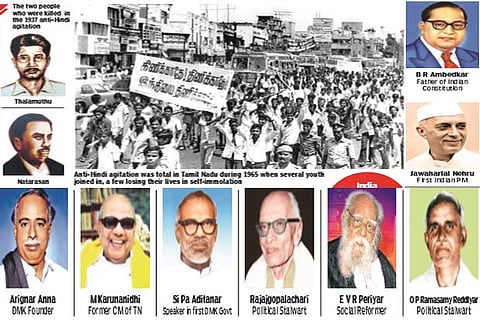

Soon after, Nehru died and the situation changed drastically as the people of Tamil Nadu did not trust any other leader in Delhi. Added to that, leaders in the north made statements to the effect that those not speaking Hindi did not have a place in the country. Also, in Delhi, all name boards were only in Hindi and all English name boards were removed. This created more anger among Tamilians and in 1965, the anti-Hindi agitation revived strongly and triggered widespread riots.

Tamil enthusiasts hoisted black flags on Republic Day and declared January 26 as black day. In north India, protests to remove English gained momentum. They said, “Those who do not know Hindi have no place in India”.

In Tamil Nadu, anti-Hindi movement took strong roots and agitators erased Hindi letters on name boards.

Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam deployed its students force and there were widespread riots. The then Chief Minister M Bhaktavatsalam took stringent action against protesters and ordered police firing against those agitating against Hindi. Several people lost their lives in police firing.

Many immolated themselves in protest. Several top political leaders who joined the agitation in support of the students were arrested. Among the stalwarts who participated in the anti-Hindi agitation were M Karunanidhi, Kundrakudi Adigalar of Kundrakudi Math, Si Pa Aditanar, who later went on to become Speaker of Tamil Nadu Assembly in Anna-led DMK’s first government, K A P Viswanatham, V R Nedunchezhiyan and professor Lakhuvanar, both leading Tamil scholars.

The agitation paved the way for DMK to come to power in 1967 defeating Congress. Even today, Congress is struggling to come to power in Tamil Nadu, such was the impact of the sentiment.

An important point to note is that Periyar did not approve of the third phase of the anti-Hindi agitation and even criticised the protesters of being politically motivated. But Rajaji who was a Hindi supporter changed his views and turned against imposition of Hindi and supported the DMK’s agitation.

Consequences ofanti-Hindi agitation

Even after Arignar Anna came to power, the anti-Hindi agitation continued. Hindi, which was an optional subject in schools, was removed by the DMK government led by Anna. Similarly, since Hindi was the language of communication in National Cadet Corps training, NCC was removed from government schools. It seemed as if Tamil Nadu was slowly moving away from the national mainstream. But Arignar Anna had no other choice but to take this decision. In 1968, then Prime Minister, Indira Gandhi, reiterated the Central government's resolve to implement the two-language policy, just as Nehru did in 1964. Navodaya schools could not function in Tamil Nadu in the 1980s because of anti-Hindi agitation. They had successfully stopped Hindi, but interest to learnEnglish picked up.

Tamil Nadu took the lead in opposing imposition of Hindi. In Maharashtra, Hindi as a language was widely prevalent and Marathi as a language had taken a back seat. But Shiv Sena's Bal Thackeray took up the cause of Marathi and brought up the Marathi Manoos issue to the fore and demanded that Marathis be given preference in jobs. Now, Raj Thackeray and Udhav Thakaray are fighting for 'only Marathi' inMaharashtra.

In Tamil Nadu, even Central government offices have to give replies in Tamil, if the citizen so desires.

Though the anti-Hindi agitation has been a much talked about topic for the past 50 years, it has not stopped students from learning Hindi inprivate schools. Lakhs of students attend Hindi examinations conducted by the Hindi Prachar Sabha. The anti-Hindi sentiment is, however, still strong with Dravidianpoliticians.

Of course, learning English has opened the gateway for Tamilians to find jobs in foreign countries. Employment and business opportunities have improved because of English. But, hundreds of people have sacrificed their lives in anti-Hindi agitations, thousands went to jail to protect Tamil language. An introspection is necessary to analyse whether Tamil language isprotected and safe.

- News Research Department

Visit news.dtnext.in to explore our interactive epaper!

Download the DT Next app for more exciting features!

Click here for iOS

Click here for Android