CHENNAI: It was 2009 in Thanjavur when Madhavi (22) and her husband Manikandan (31), a Scheduled Caste couple worked as daily-wage agricultural labourers in Vilangudi village, earning about Rs 100/day for nine hours of work. They decided to borrow Rs 30,000 for a family wedding.

Within months, that debt took them 15 km away to Devangudi, a village along the Kollidam river belt with a concentration of brick kilns.

Along with their child, the couple moved to a kiln, made a tent. And, over the next decade, they worked between 17 and 18 hours a day, cutting around 1,500 bricks daily and were paid Rs 500 a week for both of their work.

“The pain starts at the hip, then spreads to the shoulders. Hands, toes, fingers everything aches. I survived on oil, ointments and occasional hospital visits,” she recalled. There was no discussion of leaving. “We didn't talk about the future. We only talked about how much we could earn the next day and how much we still had to repay.”

By the time officials arrived in 2019, the original loan had grown to Rs 1.3 lakh. “Given the pay and our daily needs, we kept taking more loans. Life would have continued there for another decade if not for that day,” she lamented.

Madhavi remembers the date clearly: May 15, 2019, when the family was rescued. That intervention came under a law enacted long before she entered the kiln.

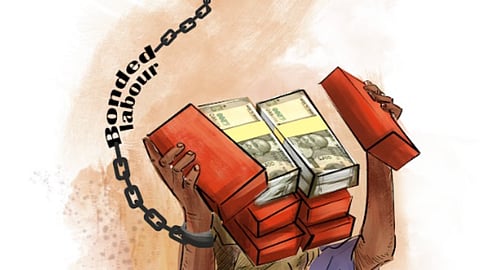

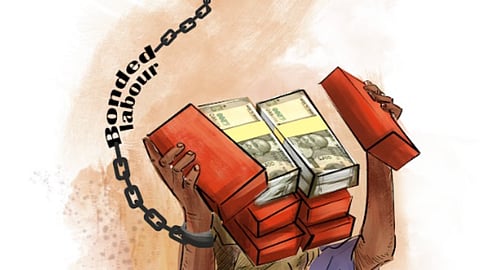

The year 2026 in India marks 50 years of the Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act, 1976, which abolished bonded labour, cancelled bonded debts and empowered district administrations to identify, release and rehabilitate bonded labourers. Since then, a lot of Union and State government initiatives, rehabilitation schemes, stringent rescue measures, and awareness campaigns have taken shape.

Yet, you could still see families living in tents. In 2024-2025, according to the State government, 330 bonded labourers were rescued and rehabilitated. Experts say a lot has improved in TN.

“The implementation of laws have come a long way,” said Pathima Raj, an activist who has coordinated with the State government on bonded and child labour for over 12 years, especially in the Delta districts. “People still fear coming forward with information, but with internet and government initiatives, identification and coordination have become easier.”

Though awareness has improved in recent years, the pattern of bonded labour has remained consistent in the Delta districts, said Pathima Raj. “Bonded labour is most visible in sugarcane fields, goat grazing, duck farming and in brick kilns,” he said. “Workers are often brought from districts such as Ramanathapuram and Cuddalore. They are unaware of their rights, held down by debt, and not allowed to move freely. In many cases, food is controlled. Caste makes them ‘unimportant’ in the eyes of employers.”

An Assistant Commissioner of Labour Department, with over 20 years of experience, said, “Bonded labour is identified based on factors such as extremely low or no wages, restriction of movement and workers being held through advances and accumulated debt. Earlier, coordination between departments was a challenge, particularly in cases involving multiple districts or states.”

Rehabilitation was handled by the Adi Dravidar Welfare Department, with revenue officials responsible for verification. “It’s not the Revenue department’s primary job to curb the bonded labourers. So, there were delays,” said the official. “Since 2017, responsibilities have been more clearly defined. The Labour department now handles identification, rescue and enforcement, while the revenue department oversees rehabilitation and cross-district/state coordination.”

Rescues typically follow complaints or field-level information. Inspections are conducted, worker statements recorded and release certificates issued, cancelling the debt under the law. Legal action, including FIRs, is initiated where possible.

Recalling a case in Pollachi, the official said, “An FIR could not initially be filed due to pressure from dominant caste groups, requiring intervention by the Human Rights Commission. Such instances have reduced, as corporatisation in some sectors has improved accountability.”

Under the Central Sector Scheme for Rehabilitation of Bonded Labourers, revised in 2021, rescued workers are eligible for financial assistance after the issue of release certificates. Assistance ranges up to Rs 1 lakh for adult bonded labourers, up to Rs 2 lakh for women and children, and up to Rs 3 lakh in cases of extreme deprivation. District administrations are also required to maintain a bonded labour rehabilitation fund to provide immediate relief.

In 2025, under the Kalaignar Kanavu Illam scheme, a tenement was allotted to Madhavi’s family. And, through the Labour Welfare Board, they have been receiving 35 kg of rice each month. Through the Child Welfare Committee (CWC), their son is staying free of cost in a students’ hostel and continuing his school education.

Tamil Nadu has also become the first state to observe February 9 as Bonded Labour System Abolition Day. “The law is the backbone for all this,” the official said.

Now back in her native village, Madhavi serves as an elected ward member. In the role, she has helped secure basic amenities for residents, including public toilets, electricity connections and drinking water supply. “I am an outspoken person, and my village people believe in me,” she smiled.