In his 1863 essay “The Painter of Modern Life,” Charles Baudelaire described the passionate city dweller as “a kaleidoscope gifted with consciousness.” In the French poet’s eyes, the city dweller had a unique opportunity to absorb and mirror the poetry of freely moving multitudes. For the committed flaneur, Baudelaire wrote, “the crowd is his element, as the air is that of birds and water of fishes.” I felt this way in New York City 15, even five years ago. Sidewalks could be strolled contemplatively, providing one kept to their right-hand side, and roads could be crossed without much trepidation.

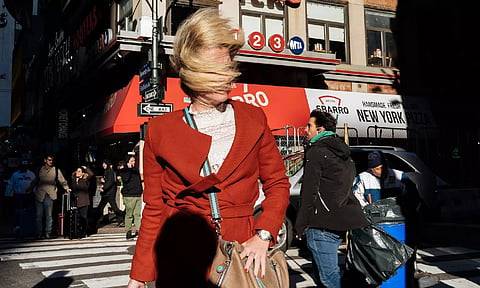

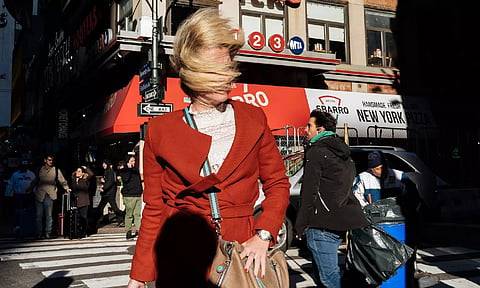

But I was hit by three bikes this past summer — two on sidewalks and all three after sunset — and only spared dozens more collisions because of my increasingly frantic footwork. In the years since the pandemic lockdown, drivers, with their ever-bigger vehicles, appear to have grown more aggressive. They seem less likely to yield to crossing pedestrians and more likely to stop, unperturbed, on crosswalks. Motorcyclists routinely whiz through red lights and tyrannize bike lanes. Bicyclists fly down avenues, bike lanes and one-way signs be damned, and a precious few of them halt for crossers. Electric delivery bikes chase poverty wages down our sidewalks, throwing the last sliver of pedestrian refuge into a novel sort of anarchy.

Weaving through throngs of inimitably colorful, diverse, bizarre New Yorkers once felt like performing “an intricate sidewalk ballet” — which is how Jane Jacobs, another famous literary flaneur, marvellously depicted the scene that was Greenwich Village’s Hudson Street in the 1950s. Today, my inner flaneur has been replaced by a neurotic curmudgeon, the likes of which Fran Lebowitz personifies in the Netflix show “Pretend It’s a City.” Lebowitz disparages drivers who stop their vehicles on crosswalks and cyclists who pay no heed to their surroundings. “I am a person who believes, every day, I have a very high chance of being killed crossing the street,” she says in the show’s pilot episode, adding, luridly, “It’s an astonishment to me that every day tens of thousands of people aren’t slaughtered in the streets of New York.”

It is an astonishment to me, too. While parts of the world have increasingly safeguarded their walkers, the United States has seen a sharp rise in pedestrian fatalities over the past few years. Deaths in New York City may not have climbed into the tens of thousands, but they remain much higher than we would like. In addition to bringing the obvious consequences of death, injury and the erosion of civic life, this citywide discord has taken a toll on emotional and philosophical life, too.

“Only ideas won by walking have any value,” Nietzsche wrote in “Twilight of the Idols.” Nietzsche, like Schopenhauer and Kant before him, took daily strolls to unravel the day’s thought-puzzles and refine seeds into concepts. There are few more effective ways to think through a philosophical or personal problem than by taking a long walk. Something about the body having been set to a task (and assigned a route) allows the mind to whir into conversation — into the inner dialogue we call thinking.

But this is possible only as long as the flaneur’s peaceable, rhythmic perambulation remains relatively uninterrupted. My own hours-long strolls through New York City have been indispensable to my literary life — I cannot finish an essay if it hasn’t been aired out over 30 blocks.