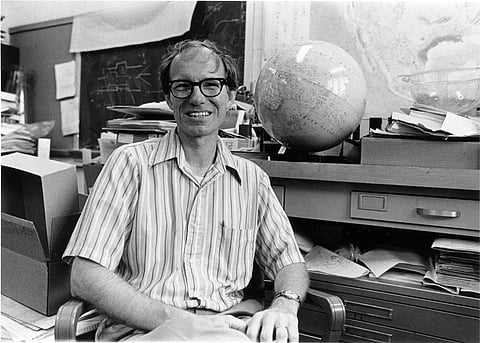

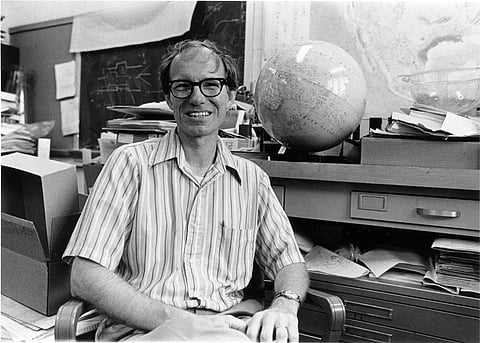

W Jason Morgan, who in 1967 developed the theory of plate tectonics — a framework that revolutionised the study of earthquakes, volcanoes and the slow, steady shift of the continents across the earth’s mantle — died on July 31 at his home in Natick, Mass. He was 87. The notion that the earth’s surface moved was not new when Professor Morgan, who taught at Princeton University, first presented his theory at a meeting of the American Geophysical Union in Washington in April 1967. People had long noticed, for example, that the northeastern edge of South America seemed to match the notch along Africa’s western coast, and wondered if they had once fit together like puzzle pieces.

By the mid-20th century, researchers had made significant steps forward in studying the movement of the earth’s surface, including the discovery that stretches of the sea floor were spreading apart. But the idea, called continental drift, remained highly debated into the 1960s, and no one had come up with a way to synthesize it all into a grand, testable framework. Professor Morgan had initially planned to discuss underwater trenches at the Geophysical Union meeting. But after reading a paper about fracture zones — vast scars across the ocean floor that offer evidence of past distortions in the earth’s surface — he changed his mind.

Looking at a map of several such zones in the Pacific Ocean, he realised that they were not random; they could be understood as a result of great plates colliding and pulling apart as they slowly moved around the earth. He also posited that the plates were rigid and fixed in shape, whereas previous theories had argued that the continents scooted around the earth on a malleable mantle. That insight made it possible to measure plate movement in the past and predict it in the future.

With just weeks to go before his talk, Professor Morgan set aside his original subject and dived into his new conjecture. He collected reams of data from expeditions to map the ocean floor, then built a computer program to test what he found against his hypothesis.

“Mom said he basically worked nonstop,” said his son, Jason, himself a geophysicist. “And she was getting a little nervous whether this was what life was going to be like, married to an academic.”

Professor Morgan took just an outline with him to the podium, along with handouts for the audience. Afterward he turned his talk into a paper, which he published in the Journal of Geophysical Research in March 1968. In the meantime, a pair of researchers affiliated with the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, Dan McKenzie and Robert Parker, published a paper in the journal Nature describing the same theory as Professor Morgan’s, though with different evidence. While Professor McKenzie is sometimes credited with discovering plate tectonics, and while he, Professor Morgan and Xavier Le Pichon, another tectonics pioneer, shared the prestigious Japan Prize in 1990 in recognition of their work, Professor McKenzie said in a phone interview that Professor Morgan “has priority” in taking credit for defining the theory.

The impact of plate tectonics was immediate. It offered a unified framework for research across the natural sciences, opening the door to new advances in seismology, volcanology and evolutionary biology.

Clay Risen is an obituaries reporter for NYT© 2023

The New York Times