NEW DELHI: When, in May, the India Meteorological Department (IMD) put out its customary pre-monsoon forecast and did not bother to disguise its anxiety over the El Nino effect on rainfall in India, we pinned our hopes to the wide margin of error the weatherman allows to himself. Now two weeks into September, we no longer have the luxury of making jokes about the Met.

India’s two wettest months, July and August, have passed, leaving the nation 11% in rain deficit. In August we recorded the lowest rainfall for the month since 2006, 36% less than the long period average (LPA), with even Kerala left high and dry.

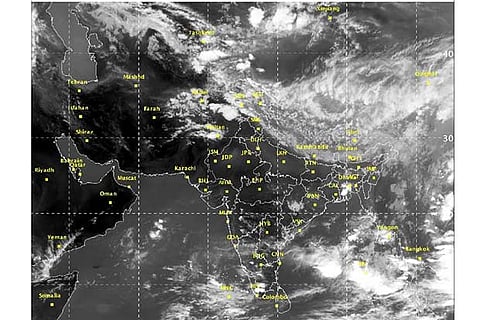

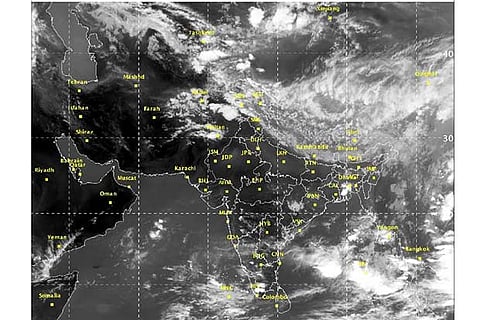

The Met divisions Central India and South Peninsular India have not had a drier August since 1901. The first two weeks of September have been only marginally better. We hear reassurances from Pune of a recovery to normal in the two weeks left for the monsoon to start receding. Sure, there has been a revival in some parts of the country, but we do have a huge cistern to fill. Mumbai has had its first three-digit rain of the season in the past week, but no less than 12 Met divisions out of 36 remain in serious deficit.

This includes large parts of eastern Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh and parts of Maharashtra. The IMD’s week-by-week rainfall map is awash in yellow, the colour for ‘large deficit’, none more than Mr Modi’s home state of Gujarat which has not seen green in more than four weeks.

To everyone invested in India’s monsoon, which includes just about every Indian, September, the month of romances and betrothals, is threatening a bitter harvest in the months ahead. Especially incumbent governments will note with alarm that the monsoons are leaving them in a vulnerable situation in the run up to the general election.

For the BJP, it must be worrisome that rain deficits are large in some of the states it rules, such as Gujarat, UP, Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh, where it needs to retain most of its existing seats to be able to return to power.

To make it worse, two fence-sitters who are potential allies of the BJP in a hung Parliament situation, K Chandrasekhar Rao and Naveen Patnaik, also rule over deficit states. The back rooms of political parties are rife with anecdotes how the Indian voter is quick to anger after a bad monsoon. No amount of mood management works when the Indian voter is angry.

Already there are reports of a greater than 30 per cent year-on-year spike in demand for MGNREGS employment. Recourse to NREGA work is a sure sign of rural distress, and the situation is likely to get worse as El Nino continues to play havoc with our rainfall into the rabi season.

The news from the Central Water Commission, which keeps an eye on 150 reservoirs around the country is no less gloomy. Storage as of last week stood at 111.737 billion cubic metres (BCM), which is 14 per cent short of the 10-year average for this time of the year. In the north, barring the flood-hit states of Himachal Pradesh and Punjab, reservoir levels are well below the 10-year average, Bihar being the worst affected. In the South, storage in 17 of the 40 reservoirs is below 40%.

Conventionally, a poor monsoon is the mother of all problems that governments hate, especially if elections fall in its wake, such as prices, water scarcity, and distress migration.

However, governments cannot fall back on the old notion of voter stoicism anymore. Social science research tells us that voter response to distress has become quicker and brutal, especially if water scarcity is widespread. If it doesn’t rain enough for the rest of September, India’s rulers have cause to be afraid, very afraid.