A GHOSAL, S ARASU

CHENNAI: The queues outside petrol pumps in Sri Lanka have lessened, but not the anxiety. Recovery has been complicated by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and the upending of global energy markets. Europe’s need for gas means that they’re competing with Asian countries, driving up prices of fossil fuels and resulting in what Tim Buckley, the director of the think tank Climate Energy Finance, refers to as “hyper-inflation ... and I use that word as an understatement.”

Most Asian countries are prioritising energy security, sometimes over their climate goals. For rich countries like South Korea or Japan, this means forays into nuclear energy. For China and India, it implies relying on dirty coal power. But for developing countries with already-strained finances, the war is having a disproportionate impact, said Kanika Chawla, of the United Nations’ sustainable energy unit.

How Asian countries choose to go ahead would have cascading consequences: They could either double down on clean energy or decide to not phase out fossil fuels immediately. “We are at a really important crossroads,” said Chawla.

Sri Lanka is an extreme example of the predicament facing poor nations. Enormous debts prevent it from buying energy on credit, forcing it to ration fuel for key sectors with shortages anticipated for the next year. Sri Lanka set itself a target of getting 70% of its energy from renewable energy by 2030 and aims to reach net zero by 2050.

How these nations meet this demand will have global ramifications. And the answer, at least in the short-term, appears to be a reliance on dirty-coal power. China, currently the top emitter of greenhouse gases, aims to reach net zero by 2060. But since the war, it has not only imported more fossil fuels from Russia but also boosted its own coal output. The war, a severe drought and a domestic energy crisis, means the country is prioritizing keeping the lights on over cutting dirty fuel sources.

India aims to reach net zero a decade later than China and is third on the list of current global emitters, although their historical emissions are very low. No other country will see a bigger increase in energy demand than India in the coming years. Like China, India’s looking to ramp up coal production to reduce expensive imports and is still in the market for Russian oil.

But the size of future demand also means that neither country has a choice but to also boost their clean energy.

China is leading the way on renewable energy and moving away from fossil fuel dependence, said Buckley, who tracks the country’s energy policy. “It might be because they are paranoid about climate change or because they want to absolutely dominate industries of the future,” said Buckley.

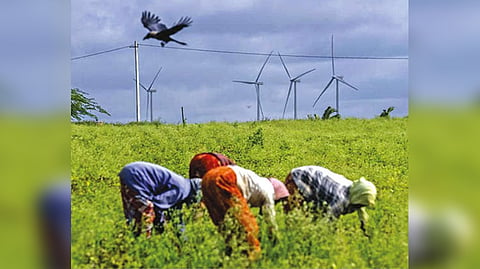

India is investing heavily in renewable energy and has committed to producing 50% of its power from clean energy sources by 2030.

“The invasion has made India rethink its energy security concerns,” said Swati D’Souza, Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis.

More domestic production doesn’t mean that the two countries are burning more coal, but instead substituting expensive imported coal with cheap homegrown energy, said Christoph Bertram at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. What was “crucial” for global climate goals was where future investments were directed. “The flipside of investing into coal means you invest less into renewables,” he said.

This article was provided by Deutsche Welle

Visit news.dtnext.in to explore our interactive epaper!

Download the DT Next app for more exciting features!

Click here for iOS

Click here for Android