Chennai

In the early 1900s two young boys, frail and dreamy, lice-ridden and open-mouthed, stood among the crowd of natives watching swimmers on the Adyar beach.

They were Krishnamurti and Nitya, sons of Jiddu Narayaniah, a retired Government official, who had moved to a decrepit house outside the Theosophical Society’s campus. Fatefully, Leadbeater, a high-ranking officer of the Society, was on the beach too. He later said that one of the boys had an unusual aura, free of selfishness which would make him a great man.

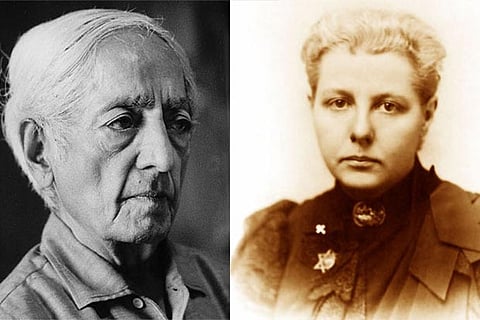

Leadbeater convinced Annie Besant that Krishnamurti would actually serve as the vehicle for the incarnation of the World Teacher Maitreya about whom theosophy was constantly speaking of. That Leadbeater himself had been recently reinducted in Theosophical Society after having been expelled amid a sex scandal involving adolescent boys was conveniently forgotten.

Annie, a more practical person, publicly claimed that Krishnamurti was likely to develop spiritual powers but was convinced that he would give the much-needed fillip to the fortunes of the sagging society. In an unprecedented move, Narayaniah was convinced to assign guardianship of the boys to her legally.

Things happened quite fast thereafter and the boys were moved inside the campus, removed from school and tutored by senior theosophists. The ‘coming Messiah’ was initiated into the occult and, in addition, they dressed him in western clothes and introduced him to the mannered formalities of European culture.

In 1910, Arundale and Annie Besant started Order of the Star in the East and its head Krishnamurti was proclaimed to be the next world teacher. The purpose was to draw together and prepare those who believed in the coming of the world teacher.

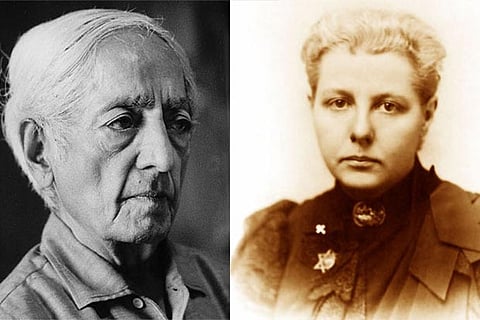

Krishnamurti, in his well-attended meetings, sometimes claimed that he was a reincarnation of Buddha. In some talks, he said he was the vehicle for the Messiah and in some claimed to be the Messiah himself. “I come to those who want sympathy, who are longing to be released, who are longing to find happiness in all things.”

The theosophical stratagem worked only well. When the concept of Messiah was thrust on a disturbed war-torn world, Krishnamurti became a cash cow for the society. Donations poured in faster than they could be counted. A Dutch even donated his estate of 5,000 acres with an old castle.

Unexpectedly, Krishnamurti’s father woke up to the financial bonanza his son was creating and wanted a slice of the pie. Narayaniah filed a suit in the District Court, Chengelpet, seeking custody of Krishna. The suit transferred to Madras High Court and was tried by Justice Bakewell.

The shrewd judge initially observed that some questions other than the welfare of the children had influenced the litigation. Justice Bakewell declared the boys wards of the court and directed Annie Besant to hand over custody of the children to the father. Besant went up to the Privy Council and managed to upturn the ruling. While Sir CP Ramaswami Iyer appeared for Narayaniah, Annie Besant argued herself.

Interestingly, Annie Besant would laud her opponent CP for unfailing fairness. The statue for Besant on the beach was later unveiled by CP. The litigation became an object of public ridicule. Mahakavi Bharathiyar wrote an English parody on Besant titled The fox with the golden tail (the blonde hair of Besant was the connection).

In a public letter to Annie Besant, Bharathi said that Indians could not “tolerate the idea of Hindus being led in spiritual affairs by a woman born in Europe and of non-Hindu parentage.”

Back in theosophy’s hold, Krishnamurti went along with the Besant screenplay till 1929. And then he rebelled. He dissolved the Order of the Star and confessed that him being the vehicle of Messiah was one big lie. He returned whatever gifts under his control to the donors but the society kept most.

For the next seven decades, Jiddu Krishnamurti carved his own path as a philosopher. He claimed that truth could not be approached by way of a teacher, and communicated his message in the riveting language and provoked inquiries into human nature and mind. He wrote prolifically and his 50 books have been translated into 40 languages. The inside story of Jiddu was told by his biographer Mary Lutyens — daughter of the architect who designed New Delhi. Annie Besant tried to project Rukmini Arundale as Devi — a replacement for Krishnamurti but found no acceptance. She died broken-hearted soon thereafter.

— The writer is a historian and an author

Visit news.dtnext.in to explore our interactive epaper!

Download the DT Next app for more exciting features!

Click here for iOS

Click here for Android