Chennai

The sprawling Presidency of Madras had speakers of many languages. And they fought tooth and nail once the Union Jack was lowered and split by linguistic borders with a lot of heartburn. And then there was always a fear from beyond the Vindhyas. Hindi wasn’t new because Rajaji had imposed it as early as 1938 (called it chutney on the plate – take it or leave it).

Post Independence, Nehru, seeing the vehemence of anti-Hindi feelings, promised the constitution would guarantee English as the language for communication for another 15 years.

In 1965 with the deadline fast approaching the prospect of the imposition of Hindi made the southern state of Tamil Nadu nervous. Ram Manohar Lohia had to cut short several of his public speeches in Hindi due to stone pelting by the audience in Madras.

With its anti-Brahmin strategy taking them nowhere, the Dravidian Movement saw a political opportunity. Using the Hindi ladder to graduate to anti-north pastures, they would turn a spark into a firestorm that would rewrite Tamil politics forever.

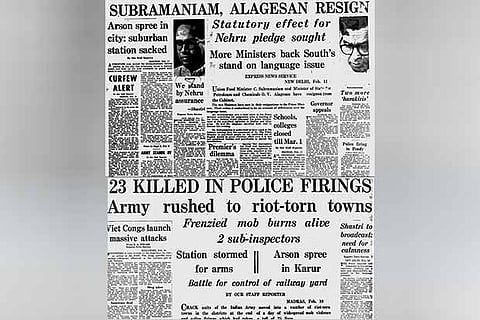

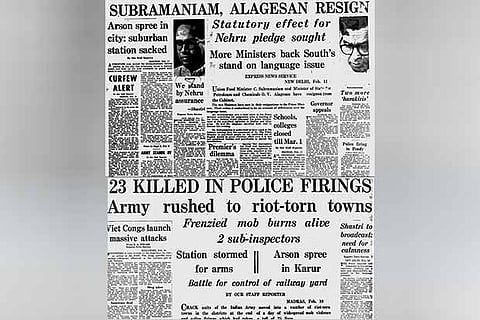

In January 1965, when DMK organised the Madras State Anti-Hindi Conference, a parallel students’ agitation turned into unrest with widespread violence. The slogan: Hindi never, English ever was scribbled on walls all over the state. In retaliation, the Central Home Minister Gulzarilal Nanda concreted his stand on imposing Hindi from January 26.

Taking up his cudgel, Annadurai announced that Republic Day would be observed as a day of mourning. (Ironically, 20 years ago, CN Annadurai chose to disagree when his mentor Periyar called August 15, 1947, as a mourning day). An alert DMK advanced the ‘day of mourning’ by a day when Chief Minister Bhaktavatsalam warned that insulting the sanctity of the Republic Day was blasphemy. Annadurai was taken into preventive custody to forestall the agitations. But the students took over and a procession of 50,000 students from various colleges in the city marched from Napier Park to Fort St. George.

Congressmen, who had fought the British, threatened the students with ‘stern action’ if they participated in politics.

Surprisingly, an ancient Tamil custom of sacrificing oneself towards a cause akin to ritual sacrifice resurfaced. Several youngsters burned themselves to death. This shocked the entire county and garnered international attention.

The Bhaktavatsalam Government saw it as a law and order problem when damage to public property became common and Hindi on name boards at railway stations was tarred.

Paramilitary forces quelled the agitation -- in street battles, two policemen died and the police shot 70 people. One of them, Rajendran, a student of Annamalai University, has a statue at the entrance of the campus (perhaps the only university that honours a student at the gates). All colleges and schools in the state were closed indefinitely.

Within the Congress, opinion was fiercely divided. K. Kamaraj wanted the government to go slow on imposition. Others like Morarji Desai wanted it implemented speedily.

Soon it became untenable for Tamil Congressmen to continue in positions of power. When Tamil ministers C Subramaniam and OV Alagesan resigned from the Union cabinet, an adamant Lal Bahadur Shastri asked the President to accept the letters but Radhakrishnan chose not to.

Shastri, finally, backed down and expressed his shock over the riots. He assured that English would continue to be used for centre-state communications.

His assurances calmed down the volatile situation. The students postponed their agitation and all cases filed were withdrawn.

The agitation had long-reaching repercussions. While many Congress leaders wanted to impose Hindi at any cost, Indira Gandhi had tried to resolve the issue amicably. She flew to Madras showing sympathy for the agitators. True to her word, she moved the bill to modify the Official Language Act in Parliament. Thus after her father Nehru, she was the first Hindi speaking leader to win the confidence of non-Hindi states.

Pro-Hindi activists were angered in North India. Jan Sangh slowly tilted right wing and its members went about the streets of New Delhi, blackening out English signs with tar. In the 1967 Madras State election, the Congress party was defeated and DMK came to power for the first time. Many future leaders were moulded by the agitation. Remarkably, Srinivasan, one of the student leaders, for whom a large number of students from all over the state campaigned, defeated Kamaraj by 1,285 votes in his hometown Virudhunagar.

— The writer is a historian and an author

Visit news.dtnext.in to explore our interactive epaper!

Download the DT Next app for more exciting features!

Click here for iOS

Click here for Android