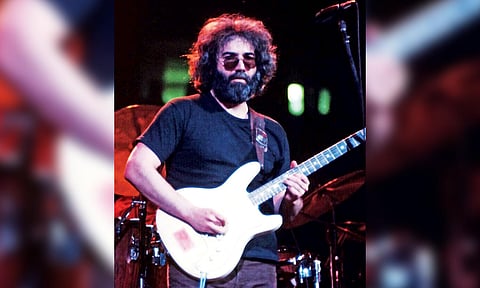

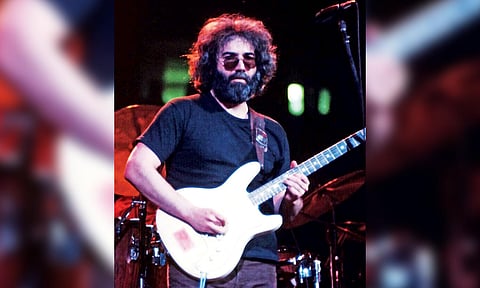

• Jerry Garcia, the iconic frontman for the Grateful Dead, remains, nearly 30 years after his death, a revered figure, singular in his approach to life and art.

A multimillionaire by the time of his death, Garcia never lost his fundamental understanding of himself as a musician, which makes him among the most relatable, if misunderstood, figures of modern times. Much of the pull he continues to exert on the culture lies in the fact that his music and his life were an exploration of what it means to be free.

He was not political, per se. Though he came of age as the American counterculture bloomed — and though he and the Dead stood at the center of many of that period’s most memorable occasions — he did his best to shun politics as such. He disdained candidates, avoided campaigns.

“We would all like to live an uncluttered life,” Garcia said in 1967, “a simple life, a good life, and think about moving the whole human race ahead a step.”

Garcia lived among artists and built up a community around him that was, psychologically and in some ways practically, impervious to government power. The Haight-Ashbury district in San Francisco offered one early experiment in community organization; Dead shows in later years stood as a kind of traveling bubble of freewheeling creativity, dynamic hubs of music and art, blissfully insulated from the outside world. It was, to Garcia, a ride on the rails — a little dangerous but happily in motion and in contact with others.

“There’s a lot of us,” Garcia said, “moviemakers, musicians, painters, craftsmen of every sort, people doing all kinds of things. That’s what we do. That’s the way we live our lives.”

He admired those who also lived beyond the government’s authority — the Black Panthers and the Hells Angels, to name two groups — though Garcia did not so much confront the government as simply refuse to accept its authority over him.

The government’s power, he insisted, was “illusory,” a myth that took real form only because people accepted it. “The government,” Garcia said, “is not in a position of power in this country.”

And yet the Dead were, Zelig-like, at the edges of the nation’s politics for decades. In 1966, they played the Acid Tests in one California as Ronald Reagan rose to power in another. They performed at the takeover of Columbia by student activists in 1968 and at Woodstock in 1969. They performed outside the San Quentin prison in California and on behalf of the Black Panthers. The Dead raised bail money for those arrested during the People’s Park uprising and, years later, for AIDS patients and rainforest protection.

But Garcia himself and the music he wrote aimed for something beyond politics, something deeper. Music was, he liked to say, his yoga, an egoless place of adventure, an open place to improvise and draw energy from the audience. It was as real as it was vivid.

The government, by contrast, was an abstraction, a collection of assertions of presumptions that fell apart under close inspection. Did the government control his music? Of course not. His community? Nope. His personal choices? Not really.

In that, Garcia was a participant in a tradition that is both noble and ragtag, alongside Walt Whitman and Henry David Thoreau, Vincent van Gogh and William Burroughs — artists who rejected social norms and conventional authority in order to practice their work and explore the range and meaning of freedom. Bohemians.

Garcia’s determination to live as a bohemian was not always honored by the government. He was arrested on drug-related charges (in New Orleans, New Jersey and San Francisco), but when it came to what mattered to him — music, community, creativity — the government didn’t hold much sway at all.

“What do they actually do that affects a person’s life?” he asked. “Not much.”

In contrast to the abstraction of government power, there was the tangible evidence of communities at work — in communes, collectives and self-contained organizations. Garcia and his bandmates spent a formative period in the Haight in the period leading up to the Summer of Love in 1967.

The Diggers, a radical collective that rejected even the use of money, organized free events and hosted a free store in the Haight, where residents could deposit food and clothing and other supplies, and where others in need could take what they needed. The “hip economy” worked. Musicians and artists brought in income, which they spent in stores (and on drugs); tourists helped support shopkeepers, concert venues and restaurants; the Diggers demanded donations and doled them out; free clinics responded to health needs.

It was not a perfect system, and as the scene grew larger and young people flocked to it, the neighborhood was unable to accommodate the influx. But it was, at least for a while, a self-contained, self-regulating community, largely beyond the reach of state and federal authorities, what Garcia called “the government.”

Even as Garcia rejected conventional government, so, too, did he abjure the most radical responses of his day. Those years in the Haight and across the bay in Berkeley, Calif., saw the flourishing of many radical cliques, especially as the war in Vietnam radicalized the Students for a Democratic Society, spinning off Weatherman and others. Some activists turned to violence.

Not Garcia. If the radical seeks to change the world, the bohemian demands to live apart from it. Garcia chose the latter.

Deadheads know what that meant. A Dead show was a place removed, a stand-alone testament to freedom. As an artist, Garcia was sublime, transformative, kinetically connected to his audience in a way that no other performer can really compare to.

Garcia’s approach to politics had its limits — and has them still. It didn’t prevent him from facing drug charges; it didn’t insulate the Dead from the local police and the Drug Enforcement Administration when it used Dead shows in the 1990s to make easy arrests of LSD dealers.

For those many people struggling today to find a place between active resistance and doleful compliance, Garcia’s life suggests an alternative: of exercising freedom rather than waiting on the government to grant it or being afraid of the government taking it away. Garcia’s legacy is more than his music, but also in his example to live freely, even as our time tests it.

(Jim Newton is the editor of Blueprint magazine at UCLA)

c.2025 The New York Times Company